My introduction to the tyranny of grammar came from an unlikely place. In my senior year of high school, I wrote a semi-fictional short story for my girlfriend. It was about us, or at least a couple that vaguely resembled us if we were ten years older, considerably more well-read, and regulars at trendy Manhattan restaurants.

It was terribly written, not to mention a total rip-off of Woody Allen. But I’d cast her in the Annie Hall role, so I thought she’d look past the obvious plagiarism and appreciate the sentiment.

In the weeks leading up to our graduation, I gave her a copy, bound with the finest brass fasteners a teenager in the south suburbs of Chicago could afford. A few days later, she returned the story covered in red ink. She’d taken the liberty of correcting my numerous grammatical errors. Her biggest grievance, as she reminded me on almost every page, was my glaring overuse of commas.

“It’s distracting,” she told me. “It’s like you put a speed bump in every sentence.”

I was stunned. How could I have been so misunderstood? She wasn’t wrong about my sloppiness with commas. I used commas like an IRA terrorist uses Molotov cocktails. I just threw ‘em in the general direction of my target and hoped for the best. But that was hardly the point. It was about passion. I’d slaved over that story all semester, locking myself in my room and blaring the Replacements’ “Answering Machine” until I'd worked myself into the perfect sentimental froth to write romantic gibberish about our three-month courtship.

I’d ripped out my heart and handed it to her, and how did she repay me? By grading my prose with the cold stolidity of a Scantron machine.

Needless to say, that was the end of us.

But it wasn’t the end of my history with comma condemnation. When I went to college, I expected an intellectual circle jerk. I wanted English professors to tell me that my fiction was Chaucher-esque, even if they didn't entirely believe it. While the faculty did have an enthusiasm for language that was lacking in my high school teachers, they also had a frustrating tendency to nit-pick about grammar. They had the hearts of poets and the brains of forensic criminologists.

I suppose I should’ve been thankful. My lackadaisical relationship with punctuation had been allowed to fester for too long. I had a childhood addiction to exclamation points, but that was mostly Stan Lee's fault. I was fanatical about Marvel Comics, and at least some of my early education in writing came from reading The Amazing Spider-Man and The Incredible Hulk. Like an immigrant who learns English by watching game shows, it eventually came back to bite me in the ass.

I didn’t realize until I was 19 that exclamation points should be reserved for very special occasions, like when somebody is shouting. And just as pot leads to heroin, casual punctuation abuse can spiral into something more serious. It wasn’t long before I was dabbling in double or even triple exclamation points. A sentence looked naked without them.

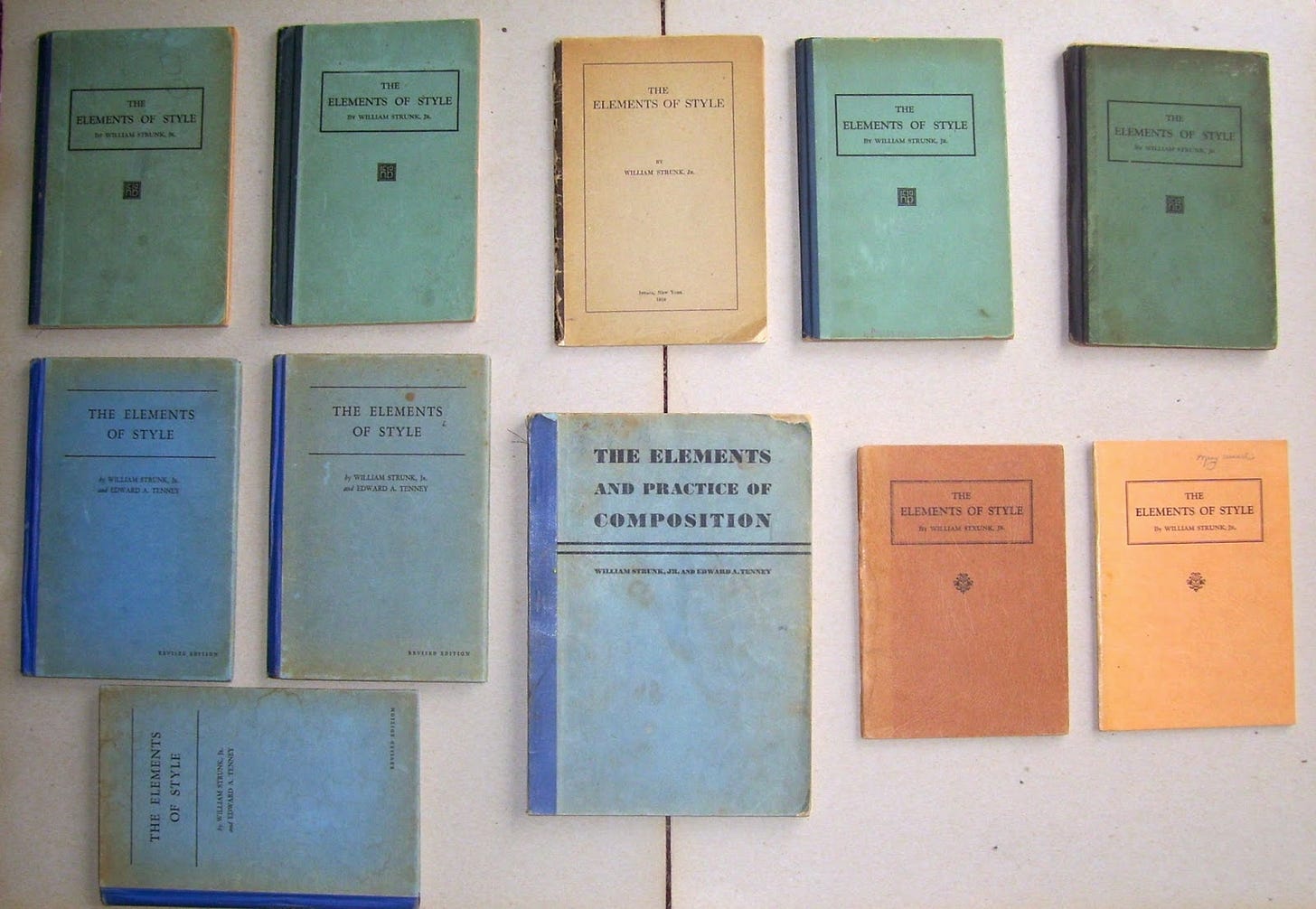

But while I gladly checked myself into exclamation point rehab, I was reluctant to sit through their sermonizing when it came to my other grammatical sins. I tried to read Strunk and goddamn White, I really did. But The Elements of Style felt like a cross between a calculus textbook and the New Testament, but without any of the sexiness. “Do this, don’t do that, put statements in positive form or God will be angry, blah blah blah.”

As a college student, there was no quicker way to ruin writing for me than reducing language to a math equation.

Strunk and White saved most of their venom for commas. Stalin didn't have this many rules. “Commas (I’m paraphrasing) can separate independent clauses when they’re joined by ‘and’, ‘but’, ‘for’, ‘or’, ‘nor’, ‘so’, ‘yet’, or after introductory clauses and phrases, but not to separate the subject from the verb or between the two verbs or verb phrases in a compound predicate.” Jesus, even writing that gave me a fucking headache.

It might’ve been easier if they phrased their cockamamie bylaws in ways I could understand. “A comma has as good a chance of getting together with an independent clause as a gay couple has of getting hitched in Alabama.” Now that I could follow.

Maybe I was being too sensitive, but it struck me as linguistic bigotry. S&W were never hatin’ on apostrophes or question marks. Parenthesis barely got a mention, even though they’re the grammar equivalent of muttering under your breath. But White, and to a lesser extent Strunk (I feel like he was the “bottom” of that twosome), had a seething loathing for commas. They were as passionate about hating commas as Alex Jones is about the cabal of global reptilian elites.

I can pinpoint exactly where I went wrong (or right, depending on your point of view). I didn’t have the best education in high school. In the 9th grade, I was struggling to understand the basics of grammar, and I couldn’t trust the textbooks we’d been assigned, which were written in the ‘60s and seemed to believe that all language had the potential to be used for communist brainwashing, so the less you knew about it the better.

I learned enough to get by, but commas remained a mystery. The textbooks offered only vague explanations: “A separation of ideas or of elements within the structure of a sentence.” I’d try to wrap my head around it by finding any metaphor that even slightly applied.

So a comma, I wondered, is like the dude at a party who introduces two people he thinks should hook up, but then he chaperones them all night, sitting between them on the couch because he's not sure if he can trust them to be alone just yet because the guy is kinda handsy. Oh, wait, no, no, no, a comma is like Nepal, a tiny country stuck between India and China, and it’s their job to... to... well, be oppressed, I guess.

I might’ve given up on commas entirely, were it not for a teacher who let an actual nugget of information slip when he wasn’t paying attention.

“A comma is when you pause to take a breath,” he told me.

It was a revelation, and for a teenager with a flair for theatrics, the worst advice anybody’s ever given me.

To my young mind, taking a breath meant pausing for dramatic effect. Every time a writer hesitated, I reasoned, they must be preparing to say something of earth-shattering significance. It was a more subtle form of exclamation points. Any hack could build tension with ellipses, but a comma seemed more... mysterious.

“You’re exhausting your sentences,” a college professor scolded me. “It’s like you’re writing with a stutter. Unless you intend this to be read aloud by Bob Newhart, it just doesn’t work.”

So I did what any reasonable person who was spending fifty thousand dollars of his parents’ money to learn what he should’ve been taught in high school would do. I ignored my teachers and added more commas.

Was I just being a smart-ass? Most certainly. But I was also rebelling against the language police, defending my independence from grammar’s fascist regime. Sure, I didn’t know what the hell I was talking about, but I felt like a modern-day Patrick Henry, albeit with a more confused idea of what constitutes oppression.

“Give me, the liberty to, take my, time with a, sentence or, give, me,,, death.”

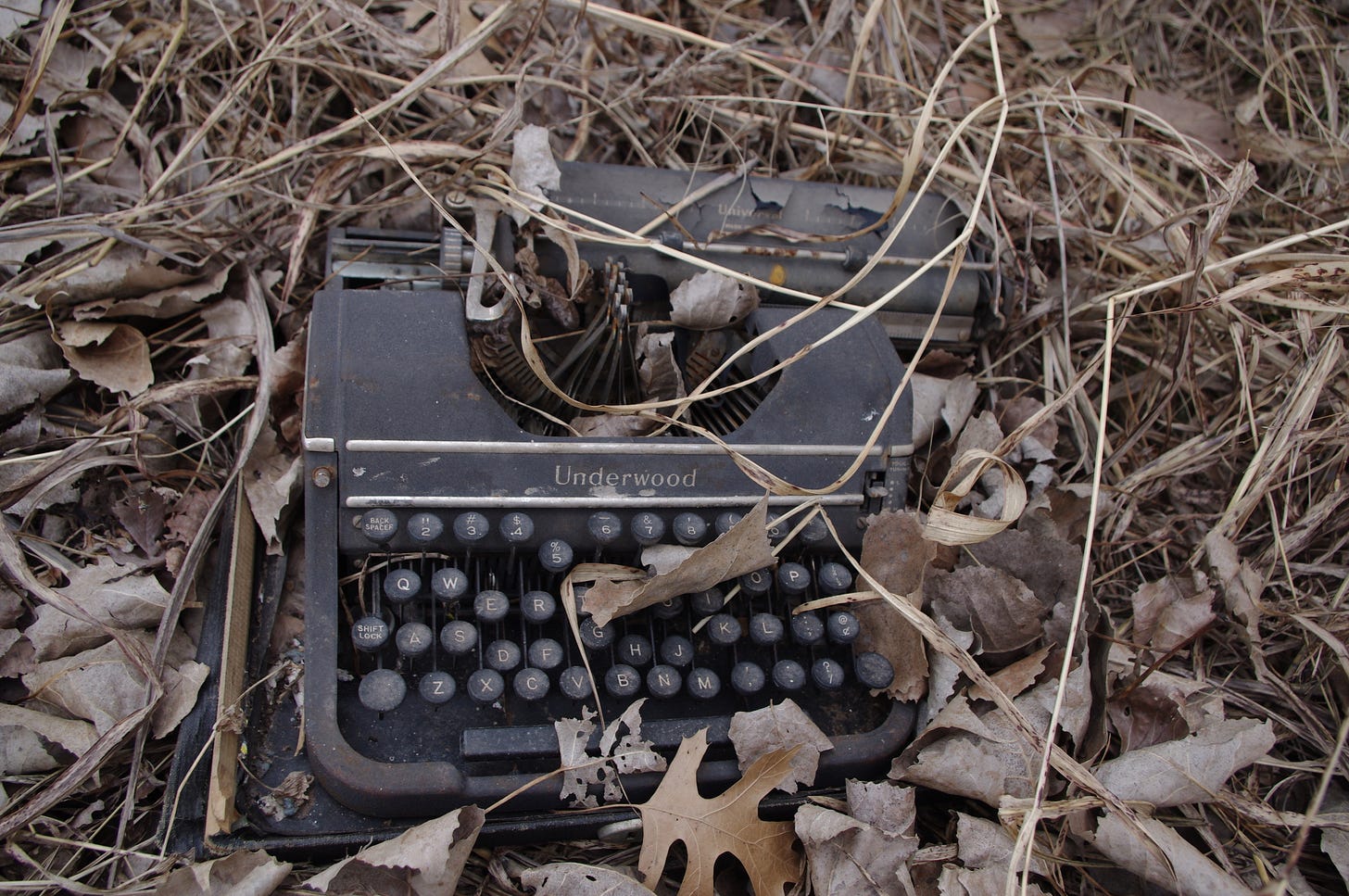

Higher education never was able to help me kick the comma habit. It took my grandfather to make me see the light. And he didn't have much to do with it either. It was his typewriter. He owned one of those classic Smith-Corona models; the kind that could be cleaned with a hose and hasn’t been modern since cars still came with a hand-crank. But he refused to throw it away, even when it started to fall apart.

His typewriter was missing several keys, including the L, the number 8, and in an unfortunate coincidence, the comma.

I learned this the hard way during a family vacation at my grandparents' Florida home. His rusty typewriter called out to me with its siren song. Whenever I sat down next to it, I was seduced by the illusion that I was in a filthy hotel room in the bad part of town, banging away at a dusty keyboard, my fingers stained with ink, a cigarette dangling from my lips, the light from a neon sign just outside the window illuminating my face in a puke orange glow.

But the dream went sour when I discovered the absent comma key. At first, my brain refused to accept it. I instinctively tapped at the empty hole where the comma key should be like an amputee scratching a phantom limb. Before long I had improvised a makeshift replacement: a Sharpie marker that made every comma look like a tumor.

I eventually gave up and went cold turkey, and let me tell you, it's exactly as bad as the junkies claim. Commas, smack, same difference. I got the shakes and a fever and I sweated through several layers of ironic iron-on t-shirts. I tried using a semicolon instead, but it felt like cheating. After the simplicity of commas, a semicolon just looked top-heavy and, well, a little slutty.

At some point, everything changed. I remember looking at one of my typewritten pages and laughing, and suddenly having a deeper appreciation for my grandfather. He loved writing letters, and I wasn't the first one in the family to notice that his letters read like manifestos. They were just one long sentence that dragged on and on. For the longest time, I thought he was going senile. But now it made sense; in a world without commas, everybody sounds like a Kaczynski.

But none of that mattered anymore. I’d stumbled onto freedom, unlike anything I’d ever known before. I was like one of those people who goes off the grid and realizes just how much the conveniences of the modern world are a crutch. Commas had been slowing me down, gumming up the works. My sentences had places to go, people to see. They weren’t gonna waste all day at a grammar tea party. I wanted to track down my old high school English teacher and tell him exactly what I thought of his precious rules. “Hey, old man, I don’t have time for your commas anymore. You think a sentence needs to breathe? I'll breathe when I’m dead!”

I spent most of my early 20s in a comma-free existence, convinced that I was following in Kurt Vonnegut's footsteps by filling my stories with super-short, concise sentences. Why say in one sentence what you can say in six? It just gives your ideas more impact. And so it goes.

But then one day an editor from a glossy magazine called me and said, “I’ll tell you what I'm gonna do. If you can rewrite this article and make me believe it wasn’t written by a post-grad asshole who jerks off to Finnegans Wake and still thinks ignoring punctuation passes for clever, I’ll bump you up to 20 cents a word.”

I said yes. I’m a professional writer, and that means my entire belief system is for sale to the highest bidder. Does that make me a whore? I guess it does. But I don’t care. You hear me, world? I don’t care!!!!!!!!!!!!

Dammit.