In Defense of Popeye, a Movie Masterpiece

Both Robin Williams and Shelley Duvall are dead, and it's high time we acknowledge their greatest cinematic achievement.

When I learned that Shelley Duvall had died earlier this month, I mourned like most fans of her film work, by revisiting some of her classic performances. But I didn’t watch The Shining or 3 Women or the beautifully bonkers Brewster McCloud. I watched Popeye, the 1980 Robert Altman musical. Because I love it, goddammit. I loved it when I first saw it in the theater as a kid, and I still love it today.

Smart people aren’t supposed to like Popeye, because it’s universally acknowledged as a hot mess and terrible filmmaking. But fuck that. It’s an amazing movie that just improves with age and, O.K., I’m going to say it: it’s Shelley Duvall’s best movie. It’s also Robin Williams’s best movie, hands down. Nothing else either actor did in their respective careers even comes close.

Let me explain.

It Makes Me Feel Stoned

Combine Federico Fellini’s cameraman, a bunch of circus performers, and some truly grotesque forearms with clearly visible blond hairs, and you have the cinematic equivalent of eating too many cannabis gummies.

Critics (and even my own friends) like to criticize Popeye for its confusing or nonexistent plot. And they’re entirely right. Too much is happening, and it’s all happening at the same time. A baby gets kidnapped, there are several frantic meals, lots of songs about nothing, characters rush in and out in pursuit of their own half-baked story lines, and at some point, Olive Oyl wrestles an octopus.

But honestly, how many times has a plot ruined an otherwise perfectly good comedy? A plot would just distract from the artful chaos and the narrative incongruities and the beautifully meaningless mayhem.

Maybe it’s an unpleasant experience for some people, but I like watching a movie and being confused and a little scared. I like thinking, Jesus Christ, the streets in that goddamn town are at geometric angles that defy logic. What am I looking at? Did Popeye just have a stroke? Wait, there’s that guy again who’s just chasing his hat. Does that mean anything? Why can’t he get his hat? Is that a metaphor for something? I don’t understand. Hey, who wants to order a pizza?

It’s Creepier Than the Cartoon

When most cartoons are turned into big-budget movies, the edges are softened. Any subversive elements—and all the truly good cartoons are plenty subversive—are ignored or whitewashed.

The original Rocky and Bullwinkle show was filled with countercultural innuendo and sly attacks on government bureaucracy. But the live-action movie, despite starring Robert De Niro, was adorable and cuddly, the kind of film that could screen at church youth group events without upsetting any parents.

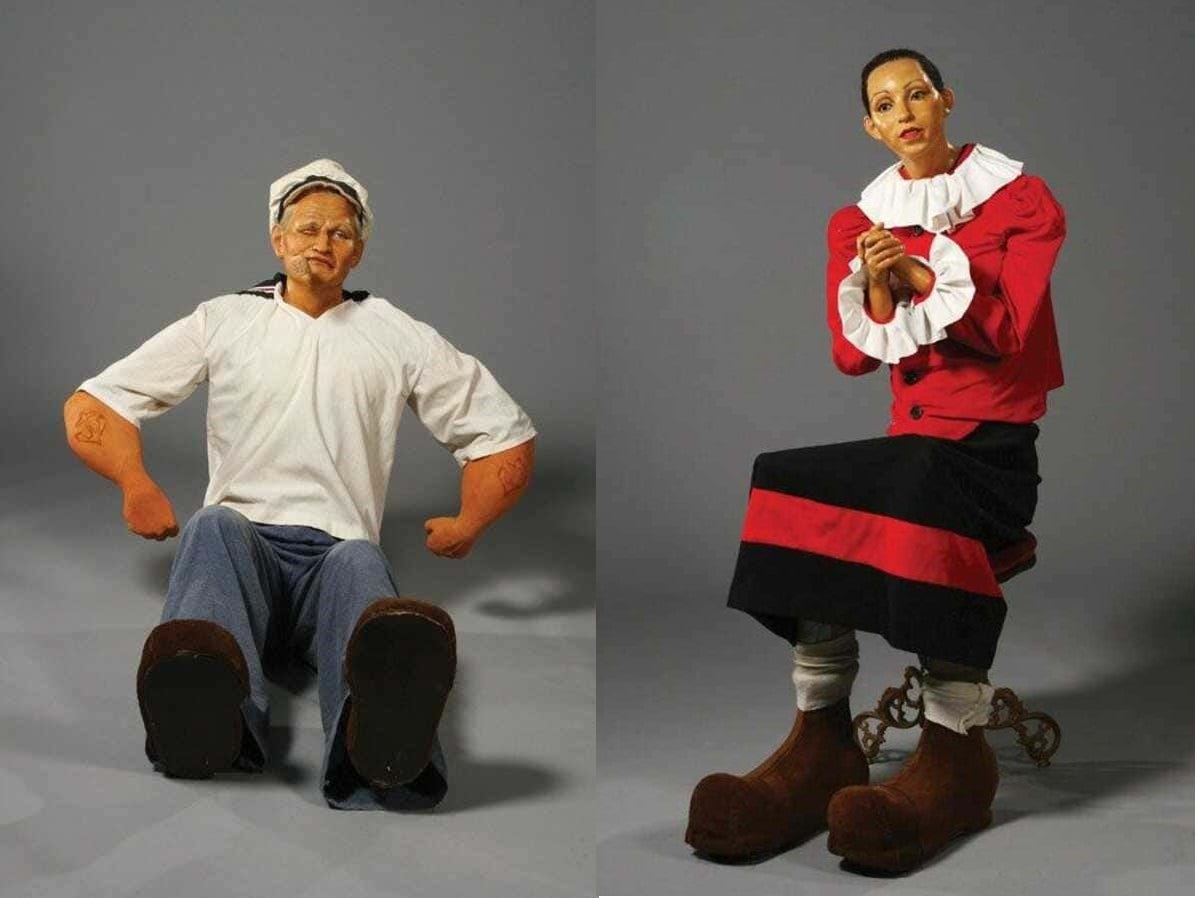

Popeye took characters that were already a little sinister and upped the ante. Popeye isn’t a cleaned-up, humanized version of the cartoon. He’s gruesome and disfigured, with a speech impediment and a painful looking squint. How did he get this way? Was he born a freak, or is he the survivor of some horrible boating accident?

His terrifying looks are never an issue for Olive Oyl, who’s clearly battling her own demons (an eating disorder), or anybody else in the town full of drunks, bullies, and diabetics.

Popeye jokes about his abusive father, who apparently used the infant sailor as a comedy prop. There’s also a scene set in a brothel, or as Popeye calls it, “a house of ill re-pukes.” That would never, ever, ever happen in any other movie adaptation of a beloved cartoon franchise. Can you imagine an Alvin and the Chipmunks squeakquel where they hang out in a whorehouse, and Alvin grapples with emotions over his deadbeat dad, who likely beat him when he was a kid? Of course not. But that would have been an amazing movie, one that should have starred David Cross.

The Soundtrack Is Freaking Genius

If you’re going to make a movie musical about a disfigured sailor in a dystopian fishing hamlet, then obviously you hire a washed-up pop musician with drug problems to write the music.

Harry Nilsson’s soundtrack is everything it should be, and exactly nothing that would appeal to mainstream audiences. All the songs are written in minor keys, so everything sounds like a lament, full of remorse and fear and barely repressed rage. The voices are flawed and scraggly, and barely make an effort beyond melodious muttering.

And the lyrics, holy Lord—what magical combination of pills and booze inspired this lyrical clusterfuck? Some songs have shades of satire (in the Sweethaven theme, the townspeople are “Safe from democracy”) and some are clumsy and perfectly imperfect (when Olive Oyl tries to sing a romantic ode to her fiancé, she can’t come up with much other than complimenting his girth).

Popeye has all the best (and creepiest) moments. When he growl-sings “I gots a lot of muskle and I only gots one eye,” it gives me goose bumps. Not the kind you get when you watch that scene with the flag in Les Misérables, but when you stupidly watched David Lynch’s Inland Empire by yourself at two A.M. and now you’re hearing creaks in your hardwood floors.

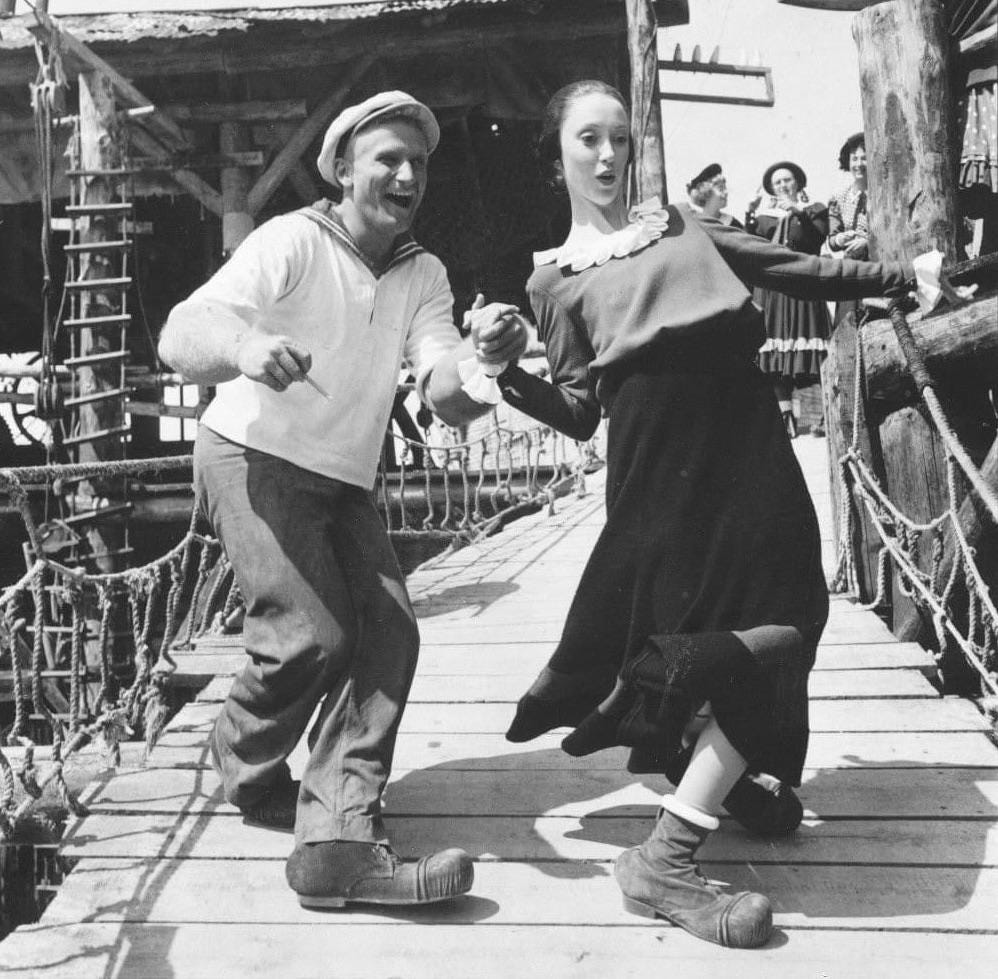

Shelley Duvall and Robin Williams Have Never Been Better Actors

Even people who agree with me that Popeye is underrated are loath to admit that it might be Duvall and Williams’s most masterful cinematic achievements. But it is.

The movie’s brilliance isn’t just in the casting, but in the unique circumstances surrounding the casting. Shelley Duvall had just wrapped The Shining before arriving on Altman’s set, and it tinges her performance. There’s something damaged about Olive Oyl, and it’s not just because she’s written as a tragic character. There are moments when she looks jittery and on edge, like she half believes all the men in her life, both Bluto and Popeye, have secret designs to murder her in cold blood.

There’s a similar weirdness to Williams’s performance. Yes, he does a perfect imitation of Popeye. But it’s not a caricature. It’s not over the top and ridiculous, like we might expect from Williams, or really any actor doing a cartoon character.

John Goodman never had less nuance and subtlety than when playing Fred Flintstone. Robert De Niro was all broad strokes and campy delivery in The Adventures of Rocky & Bullwinkle. But Popeye had a shy and timid sweetness. Williams didn’t storm through the movie with an insistent likability and “look-at-me” bombast. He was mostly reacting to all the freaks zigzagging around him.

It was a quiet artistry reminiscent of Peter Sellers’s best film, Being There. And like some confused people will insist that Sellers was better in the Pink Panther movies, fans of Williams will almost always argue that Good Morning, Vietnam or Dead Poets Society were better movies. They were certainly great movies, but they were also easy. Not easy for people like you and me, I mean specifically for Robin Williams.

Popeye is Williams actually acting, long before anybody knew he could act, in a movie in which nobody could have blamed him for not even hinting at his character’s frailty and humanity. The bar has never been lower for him, and yet there are moments in the movie of legitimate tenderness and aching vulnerability.

I’ll take Popeye gentle cradling Swee’pea in his freak arms, as he tries to reconcile his daddy abandonment issues and just how truly alone he feels in the universe, over a bearded Williams making Matt Damon cry in therapy any day.