Is DNA the Reason I’m So Damn Cheap?

Looking for the bright side in a family history of frugality

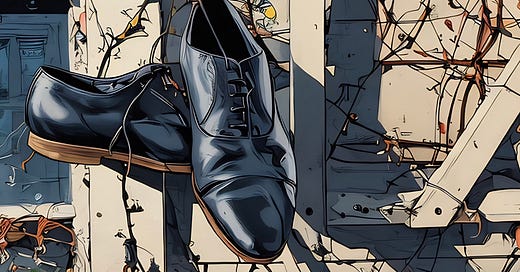

As I write this, I’m wearing my dead father’s shoes.

They’ve definitely seen better days. I couldn’t even tell you the brand anymore, they’re so worn out. But I keep them shined anyway, like my father always did. It may be the equivalent of taking a rusty Plymouth Valiant through a carwash, but I do it anyway, because I like the ritual of it.

I feel self-conscious sometimes when I wear them—and I’ve worn them to almost every formal occasion in my life, including my wedding—because I know people are looking down at my feet and thinking, “Did he steal those shoes off a dead hobo?”

Part of the reason is sentimentality—my father passed away two decades ago—but that’s not a good excuse. There are better ways to remember him. It made sense to wear hand-me-down shoes when I was young and broke, but I’m in my 50s now, with enough disposable income to afford a decent pair of shoes. What the hell is wrong with me?

That’s a rhetorical question. I know exactly what’s wrong with me. I’m a cheapskate.

My wife reminded me of this just the other day, when I returned from a trip to the grocery store. “Did you steal this from a soup kitchen?” she asked, examining the contents of my bag.

“What?” I asked, incredulous.

“Look at this spaghetti sauce,” she demanded, holding up a can. “It doesn’t even have a name on the label. It just says ‘spaghetti sauce.’ It’s so generic, nobody wants to take credit.”

This was not a one-time occurrence. It happens more than I’d like to admit. I’ve been known to get a haircut by a nearly blind elderly barber just because he charges Depression-era prices, and purchase (at an incredible discount) four dozen rolls of one-ply toilet paper so thin that adding any moisture whatsoever causes it to instantly evaporate. (I refused to throw it away. We still have a few rolls in our bathroom closet, and dammit, we’re using every last translucent inch.)

I always defend my tightwad choices, and my wife always says the same thing. “It’s fine, I keep forgetting you have your family’s cheapness gene.”

I used to be able to laugh this off. But lately, my obvious cheapness feels less like an adorable quirk and more like a red flag. I’ve become the pale-skinned guy who’s been sitting in the sun his entire life, and is only now starting to wonder if his family history of skin cancer is something he should be worried about.

Being frugal with money is part of my family’s heritage, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It means every generation, on both my mom and dad’s side, have had retirement savings and stellar credit. But it’s not just about financial responsibility. Give any of my relatives $20 and they’ll bury $19 in the backyard and then use the rest to buy mayonnaise from a dollar store.

They’ll eat anything if it costs less than a dollar. It doesn't matter if its main ingredient is rat feces and the packaging is covered with FDA warnings about a direct connection to nine different types of cancer, they’ll make a meal of it if they can pay in penny rolls.

When I was a kid, I didn’t have nightmares about monsters lurking under my bed. What made me shiver as I tried to drift off to sleep was the thought of my uncle kicking down my bedroom door and roaring, “Good news, I just snatched three pounds of frozen shrimp from the dumpster behind Meijer's!”

I’m sure that nobody in my family would characterize themselves as cheap. But racists never think they’re racists either. A racist never says, “The only one more racist than me is my father and grandfather. Everything I learned about racism, I got from them. We are such a racist family!” They may think cheapness is a virtue, but they’ll never come right out and self-identify as the “C” word.

I’m right there with them. I’ve lived in denial for years. For most of my adult life, I was sure that cheapness was something everybody else in my family struggled with, but not me. I’d snicker when they’d show up for Thanksgivings with a turkey the size of a child's fist, or they’d exchange Betamax tapes of movies they’d recorded from TV. When my grandfather celebrated his 70th birthday by re-shingling his house—not to prove that he was still self-sufficient, but because roofers were crooks—I thought it was hilarious.

But as I’ve grown older, it’s become increasingly obvious that I’m not immune. I’ll be out for drinks with friends, and we’ll decide to split the bill evenly, and I’ll start recalculating the math in my head. “I didn’t have any of those nachos, and my drinks were $2 less than what he ordered, so I’m paying at least $8 more what I owe and oh my god I’m becoming my grandfather!”

Was it inevitable? Maybe this instinct to protect every dollar, like a grizzly mom slashing the faces of hikers to protect her cubs, is just hardwired into my DNA. When I see meat in the grocery store that’s “priced for quick sale” and my first thought is, “I should buy some of that,” I might just be responding to the genetic programming of countless generations of Spitznagels.

But it could also be nurturing. Maybe I was born with a clean slate, but after a childhood of watching my parents and grandparents duck restaurant checks with Fred Astaire grace, it became my new normal. Without ever being explicitly taught, I know how to avoid a check like a grifter. I know when to excuse myself post-meal for a bathroom break, and when I get back I’m like, “Oh shoot, you already paid? Okay, I’ll get it next time.” That’s not a skill you’re born with. You learn that from getting raised by professionals cheapskates.

Stephan Siegel, a business economics professor at the University of Washington, has studied the role of genes in financial behavior, and whether our relationship with money is more influenced by nurture or nature. I explained my concerns to him, but he wasn’t able to give me a satisfying answer. “It’s not like hair color or height or eye color, which are determined directly by genetics,” he said. “But because of the way our brains are built, it’s at least partly influenced by the genetic makeup.”

“So it’s nothing my parents taught me?” I asked.

“Not really,” he said. “From our research, we found that parents have a big impact on how their children think about money very early on, but the influence tends to drop off as the children grow up. Once people reach 35 years old, it’s largely gone. It’s genetic composition that continues to matter.”

It’s not my dad’s fault, it’s my great-great-grandfather's fault. Or rather, his DNA. That’s the reason I’m still wearing my dad’s shoes, which are always on the cusp of falling apart like a barn in a hurricane.

I needed a second opinion, so I called my younger brother Mark and invited him to lunch. “I’m buying,” I told him.

That was a joke, of course. There was no way I was buying.

I had a good reason for expecting my brother to pick up the tab. Mark is rich. He’s very, very rich. Like Daddy Warbucks or Lex Luthor rich. He runs the hedge fund Universa Investments, a company with assets in the billions. He’s got two homes in Michigan, a goat farm, and an office in Miami. I rent a small three-bedroom apartment in Chicago, and I store our extra stuff in the garage. We are the yin-and-yang of financial independence.

Mark was the first person in our family to make meaningful money. Not that every other Spitznagel has been a pauper. We’ve done okay. But Mark has reached a different economic stratosphere. We’ve talked about his bizarre wealth, but always in a big brother teasing his younger brother sort of way. My questions never go deeper than, “Do you take baths in gold coins now like Scrooge McDuck?”

I’ve never been that interested in how my brother got rich. I know the basics. As he’s explained it to me, “I arbitrage different intertemporal moments—the present moment versus a future moment—against each other, taking advantage of people’s extreme hyperbolic discounting.” Which as far as I’m concerned, might as well be the muted trombone "mwa mwa" of a Peanuts parent.

Mark knows what “ intertemporal arbitrage” means, which is why he can afford to buy a helicopter and I absolutely cannot.

But we’ve never discussed money on a more personal level. Has he ever felt the tug of our family’s cheapness gene? And if he does, has he ignored it? Maybe the reason he’s rich and I’m still living from paycheck to paycheck is because he found a way to break free from our family’s self-destructive patterns.

“Cheapness is actually a really great instinct for an investor,” Mark told me.

“That doesn’t make any sense,” I protested. “Aren’t you making huge, potentially catastrophic financial bets?”

“Not really,” he said. “Successful investing is about paying less for an asset than it’s ultimately worth. It requires being ‘cheap’ when it comes to price.”

“So it’s like when our parents used to buy groceries, and we’d tell them, ‘The expiration date on this tuna is from last month,’ and they'd say, ‘But do you know how much we saved?’”

“Not really, no.”

“Different things?”

“Very different.”

After a full morning of my brother trying to explain what he does for a living, and me trying to force connections between whatever it is he does and our family’s unwillingness to spend any more than absolutely necessary, we both gave up. I signaled the waiter for the check, and then pretended to read an important email on my phone while my brother paid the bill. Then he glanced at the floor.

“Are those Dad's?” he asked.

“Yep,” I said. I held up my feet, letting him inspect the freshly-buffed shoes. “You still have yours?”

Our dad had several “favorite” pairs of shoes, which my brother and I inherited after he died. Mark won’t wear his—I guess it's hard to be a convincing investor when you’ve got toes peeking out of ripped leather—but he still keeps them in a ginormous closet in his ginormous house. And like me, he shines them every day.

Mark told me how his daughter recently discovered the shoes, and she had many questions about her absent grandfather. She took the shoes, hiding them in her bedroom, and studying them like they had mysteries that’d be revealed if she just stared at them long enough.

One night, when our mother was babysitting, she told my niece a story, one that neither Mark or I had heard before.

It was a story about our great-grandfather, who was a farmer in Germany. After a terrible drought, he and his family gave up and moved to America. They tried farming again, and our grandmother would sit in the back seat of their Model T Ford and hold onto crates of eggs as they drove to the market, but she somehow always end up with cracked yolk on her face. They gave up on farming yet again, and started a shoe business in a little red house shaped like a barn, and lived in the attic above the store.

Our grandmother grew up and met a man studying to be a doctor, but his patients were too poor and could only afford to pay him with chickens. So they moved into the attic above the little red house shaped like a barn and had a son, and eventually scraped together enough money to buy their own home. But they always came back to the little red house shaped like a barn, and when their son was old enough and ready to go out into the world, they gave him a shiny pair of shoes from that store, which was the reason he never became a farmer or had egg yolks splattered on his face during long, bumpy car rides.

Our dad held onto those shoes from the little red house shaped like a barn, even when he got married and became a dad to two sons. When he died, he was wearing the shoes from the little red house shaped like a barn, given to him by parents who had passed away years earlier. And now my brother and I had those shoes, and we carried them with us like heirlooms. Something about those old shoes felt familiar and safe, even if we couldn’t tell you exactly why.

It's not really the answer I came looking for. It didn’t explain everything. I’m still not sure why my family has such an aversion to expensive jam, to the point where they’d rather be caught with a dead body in their car trunk than rewarding themselves with overpriced fruit preserves.

But the story of the shoes still felt like enough. Because for the first time, my family’s frugality didn’t seem like weakness. It wasn’t about steeling ourselves for inevitable tragedy. “Let’s hoard some canned food in the basement, just in case the apocalypse is coming!” That may be where it all began, the survival instinct that’s been drilled into our DNA, and why I go out to buy milk and immediately think, “I bet it’s cheaper at the Rite Aid.”

But it’s evolved into something more. The next time I wear my dad’s shoes, I won’t cringe when people stare disbelievingly at my feet. Yes, they’re ridiculously old shoes. They’ve got John Steinbeck Dust Bowl grime on them. But there are family secrets in those old soles.

Sometimes we cheapskates cling to things not because we’re afraid of the future, but because they keep us connected to the past.