It’s 6 a.m., and my balls are the temperature and color of a blue raspberry snow cone.

I’m sitting on a deck chair on my open-air back porch, which overlooks an alley and half a dozen houses. It’s late January in Chicago and the weather is a nippy 24 degrees. On any other day, I wouldn’t even consider walking outside without a down jacket and mittens, or at the very least pants.

But today, I’m wearing shoes. Just shoes.

I cross my legs in case a neighbor happens to glance out the window. The wind is slicing into my frightened, exposed flesh. I’ve only been sitting out here for 20 minutes, but hypothermia feels like a very real possibility.

I try to distract myself with my notebook and pen. I’m not just some masochistic nudist wondering how quickly genital frostbite sets in. I’m here with a mission. I’m trying to find out if acting like Benjamin Franklin can make me think like Benjamin Franklin.

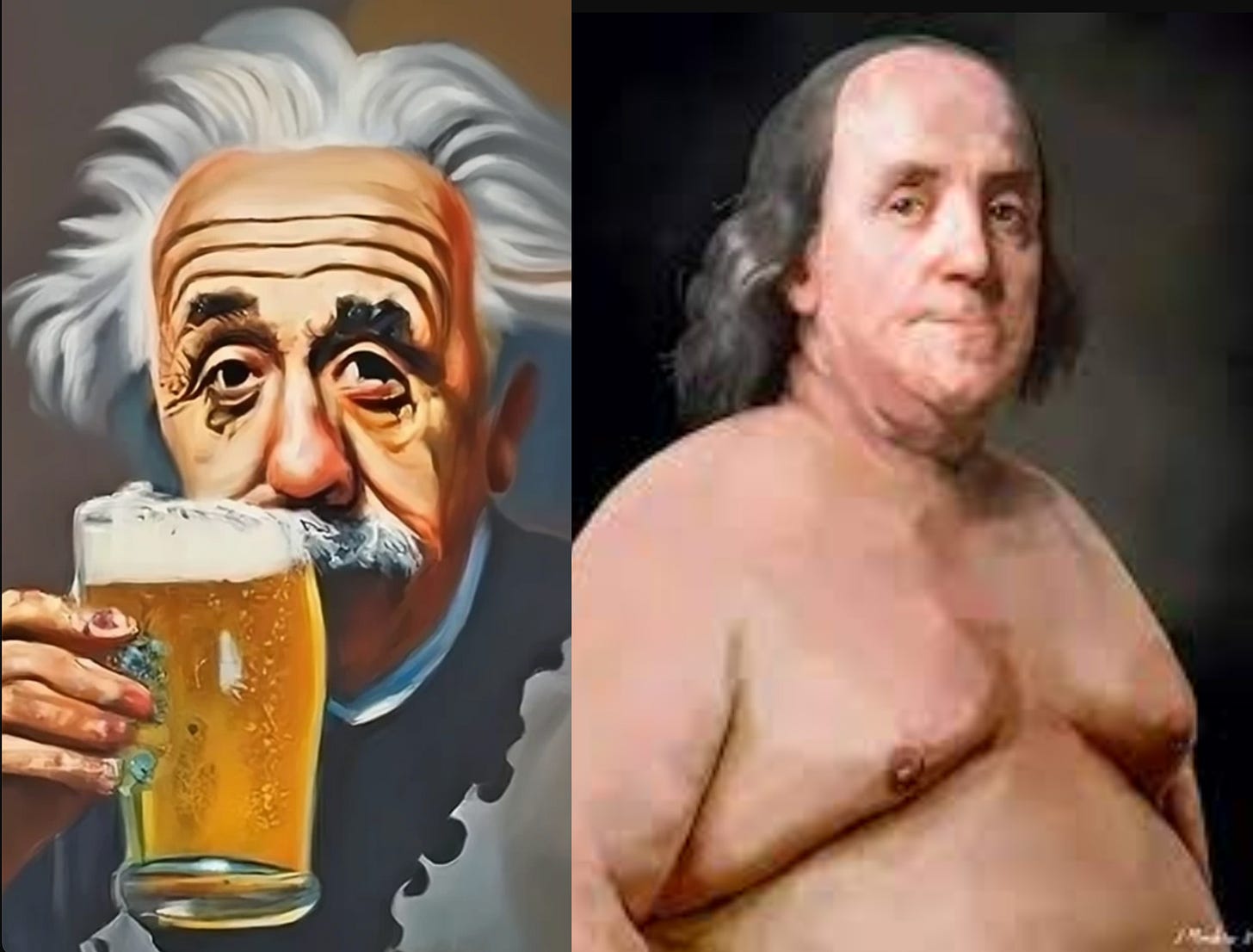

Franklin was unquestionably a genius, not just as a politician and diplomat—he helped draft the Declaration of Independence—but as an inventor, writer, and deep thinker. He also thought he was at his most productive when naked and cold.

Franklin would begin a typical working day by sitting in his chamber, next to an open first-floor window “without any clothes whatever,” he wrote to a friend in 1768, “half an hour or an hour, according to the season, either reading or writing.” Who knows what ideas came to him during those morning “air baths,” as he exposed his shriveled, frosty man bits to the world?

Franklin wasn’t the only brilliant mind with some bizarre work habits. Composer Igor Stravinsky stood on his head for fifteen minutes each morning to “clear his brain.” Charles Dickens wrote with a compass so he could be sure he was always facing north. Inventor Nikola Tesla would curl his toes one hundred times on each foot as a way of stimulating his brain cells.

Hunchback of Notre-Dame novelist Victor Hugo started his work day by eating two raw eggs, Rocky Balboa-style. David Bowie survived during the mid-1970s on a diet of cocaine, milk, and hot peppers. Einstein refused to wear socks. Are geniuses just more prone to quirky habits, or did their quirks fuel their genius? And if it’s the latter, can you train your brain to think like them?

It’s possible, says Scott Barry Kaufman, Ph.D., the director at the University of Pennsylvania’s Imagination Institute and author of Wired to Create: Unraveling the Mysteries of the Creative Mind.

“The key is to put yourself in a space that shifts your thinking,” he says. He points to 2012 research from the Netherlands, which found that any abnormal or jarring life experience, good or bad, can inspire creativity.

“Unusual experiences are good for the brain,” Kaufman says. “Geniuses only seem quirky to others because they don’t have trouble risking madness.”

So I wondered: What if I followed in the footsteps of geniuses, forcing myself out of my usual routines? Could I become the next Ben Franklin? I decided to find out.

Here’s part one of my ongoing investigation into whether acting like a genius can turn you into a genius or just another idiot without pants.

1: Cold and Naked

Prominent Practitioners

Franklin’s air baths never caught on with his fellow Founding Fathers, despite his insistence that the practice was “not in the least painful, but on the contrary, agreeable.” But across the Atlantic, in Vienna, Austria, composer Ludwig van Beethoven had adopted a strangely similar custom. While composing, he would take breaks to dunk his head in ice-cold water or pour an entire pitcher over his head, while humming loudly to himself. He often had to find new places to live, as the water would leak through the floorboards into the home of a downstairs neighbor.

The Test

I did feel more inspired and productive, probably because I knew the sooner I got something done, the sooner I could get back inside and put some clothes on. Anything below freezing, however, and my notebook was filled with expletive-laden gibberish. But at around 45 degrees, uncomfortable but not ridiculous, my head felt clearer and more alert than at any other point during the day.

The Science

Researchers disagree. A Cornell University study was pro-warmth, finding that workers at a Florida insurance company made 44 percent more mistakes when the office thermostat was set lower than usual. But researchers at the University of Virginia and the University of Houston found the opposite. Subjects performing simple tasks in rooms with warm temperatures “had depleted cognitive resources,” says Vanessa Patrick, the study’s co-author. “But cool temperatures facilitated a more open, abstract, and risk-seeking mindset.”

Decreased comfort, whether your comfort zone is chilly or balmy, can “create a sense of urgency, or push the brain and body into survival mode,” says Yohan John, Ph.D. a neuroscientist at Boston University. “If creativity involves fresh perspectives and thought processes, then any sort of environmental change has the potential to trigger it.”

It’s possible that the “short sharp shock” of a burst of unpleasantly cold water can hit the reset button on our brains, he says.

2. Staying in Bed

Prominent Practitioners

In an interview with the Paris Review in 1957, Truman Capote called himself “a completely horizontal author. I can’t think unless I’m lying down.” The French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes spent his mornings working from bed, and James Joyce would lie on his stomach in bed and compose books with a large blue pencil. Other big minds who got some of their best ideas under the covers include Voltaire, Marcel Proust, Winston Churchill, Jack London, Vladimir Nabokov, and Brian Wilson.

“Just try it in bed sometime,” Mark Twain insisted of his bed-writing habits to the New York Times in 1902.

The Test

I climbed into bed dressed in a suit and tie, so I wouldn’t forget that I was there to work. Instead, I felt like the main attraction at a wake. It was difficult to concentrate at first, and I took what might be considered an excessive number of naps. But when I was awake, the ideas came fast and furious, likely because I was so well-rested.

The Science

Makes sense. Bernd Brunner, the author of The Art of Lying Down: A Guide to Horizontal Living, claims lying down allows your body to use less energy, so it can be “better focused on intellectual pursuits.”

An Australian study found that being horizontal helped participants solve word puzzles 10 percent faster than those who stood. Darren Lipnicki, Ph.D., one of the researchers, explains: On your back, “the heart beats slower, and less noradrenaline is released in the brain.” And noradrenaline, a neurotransmitter, can impair different types of cognitive processes, like creative thinking.

He notes that an anagram solution often “suddenly pops into the mind like the ‘ah-ha’ moment of creative breakthroughs.” So: “Being able to solve anagrams faster when lying down suggests that creative thinking might also be facilitated in this posture.” Voila!

3. Booze

Prominent Practitioners

Ulysses S. Grant won the Civil War while almost constantly hammered on a private stash of whiskey. Orson Welles was known for his “gargantuan consumption” of booze, according to his biographer. Painter Jackson Pollock was “drunk almost every day and night” of his life, claimed one art critic. Ernest Hemingway drank so much that fellow author George Plimpton once claimed you could “see the bulge of [his liver] stand out from his body like a long fat leech.”

The names go on and on. Dickens, van Gogh, Picasso, Twain, Beethoven, Dorothy Parker, William Faulkner, and Tennessee Williams were all lushes. Alcohol and genius just seem to go hand in hand.

The Test

Researchers at the University of Illinois at Chicago determined that a blood alcohol content (BAC) of exactly .075—just shy of the legal limit of 0.08 (in most U.S. states)—was the perfect amount of intoxication for problem-solving and out-of-the-box thinking. I bought a Breathalyzer and proceeded to drink till I hit the magic number.

It’s not easy. At five beers, my BAC was .044, but by beer six, I’d rocketed to .069, so I tried to slow down and within ten minutes, I dropped to .038. At ten beers, I’d lost the Breathalyzer and was watching ESPN while eating microwave popcorn.

The Science

Inconclusive. Do smart people drink? A lot of them do. According to a 2015 Gallup poll, 80 percent of college grads describe themselves as drinkers, while only 52 percent of adults who ended their formal education with a high school diploma consume alcoholic beverages.

A 2013 study of nearly 50,000 Swiss males between the ages of 18 and 22 found a link between a high IQ and moderate drinking. But the brilliant people who are drinking to excess aren’t doing themselves any favors. Research published in the British Journal of Addiction back in 1990, which investigated the heavy drinking of legendary writers, artists, and composers from the 20th century, revealed that their drinking proved detrimental 75 percent of the time, and only provided a creative or career advantage 9 percent of the time.

“There are certainly writers who are alcoholic and went off the deep end,” says Stanton Peele, Ph.D., a psychologist and author of 12 books on addiction. “But it is at least equally good to say, not that drinking helped their writing, but that writing helped their drinking.”

4. Sleep Deprivation

Prominent Practitioners

Franz Kafka rarely slept while writing books like Metamorphosis, about a guy who turns into a cockroach after not being able to fall asleep. Thomas Edison and Leonardo da Vinci slept only during 20-minute naps throughout the day, just enough to feel kind of rested but not really. Inventor Nikola Tesla slept only two hours every night and had a nervous breakdown by age 25. But then he invented radio and electric motors, so maybe it was worth it.

The Test

Forty-eight hours of sleeping in 20-minute spurts didn’t make me more alert and creative, just more unhinged and emotional. I cried at everything — dropping my kid off at school, kind emails from colleagues, Google commercials — with the kind of epic weeping usually reserved for a parent’s funeral. I also got into a hysterical screaming match with my wife about who was supposed to empty the dishwasher.

The Science

Iffy. “Your creativity wouldn’t benefit from trying to sleep deprive yourself,” says Deirdre Barrett, Ph.D., a Harvard psychologist and author of The Committee of Sleep: How Artists, Scientists, and Athletes Use Their Dreams for Creative Problem Solving. “Quite the contrary.” Getting less than an optimal amount of sleep—seven to nine hours a night—could mean scoring lower on several measures of cognitive function including creativity, she says.

But even if you’re not normally awake at 4 a.m., there may be some benefit to an insomniac’s schedule. Mareike Wieth, Ph.D., a professor of psychological science at Albion College, studied how people solve riddles during “non-optimal” times, and found that people are better at thinking creatively, as opposed to analytically, when they’d rather be in bed. Why? Because they are easily distracted and can’t focus on just one problem.

“Seemingly unrelated thoughts enter your mind,” she says. “And that can lead to outside-the-box thinking and creativity.”

[Check out part two by going here.]