Game one of the World Series begins tomorrow night, between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the New York Yankees. I have no clue who’ll win—the Dodgers are favored by Vegas oddsmakers—but I do know this: This will be the first World Series since 1981 in which both teams don’t have a mascot.

The Dodgers hired a mascot in 1957, a sad-sack clown named Weary Willie (played by Emmett Kelly), but promptly fired him the following year when the team moved to California.

The Yankees one and only mascot lasted a little longer, but weirdly, he’s almost entirely forgotten.

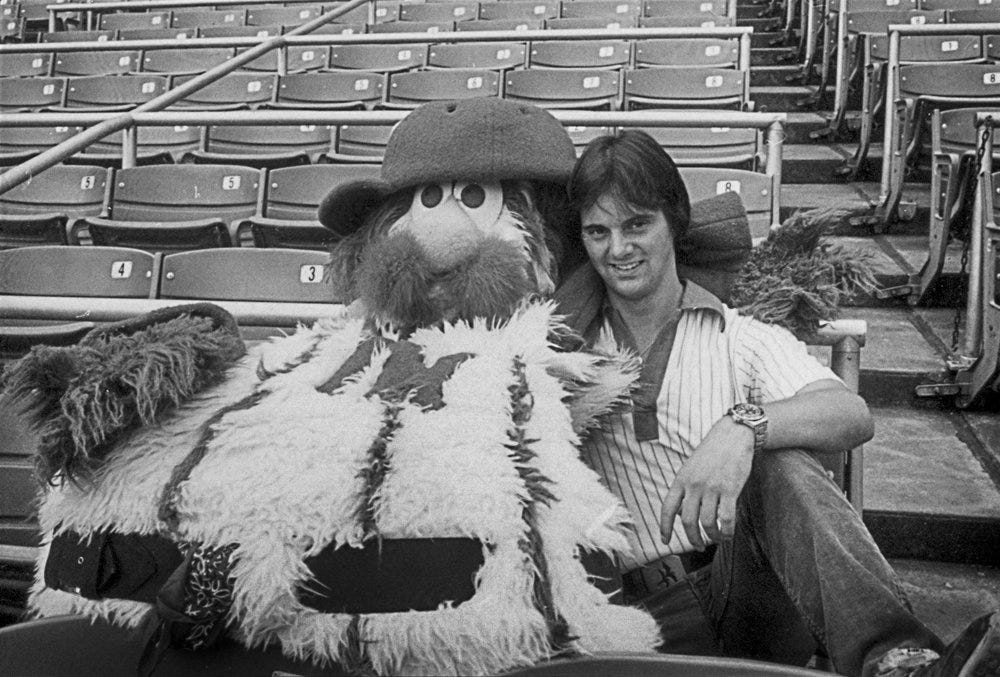

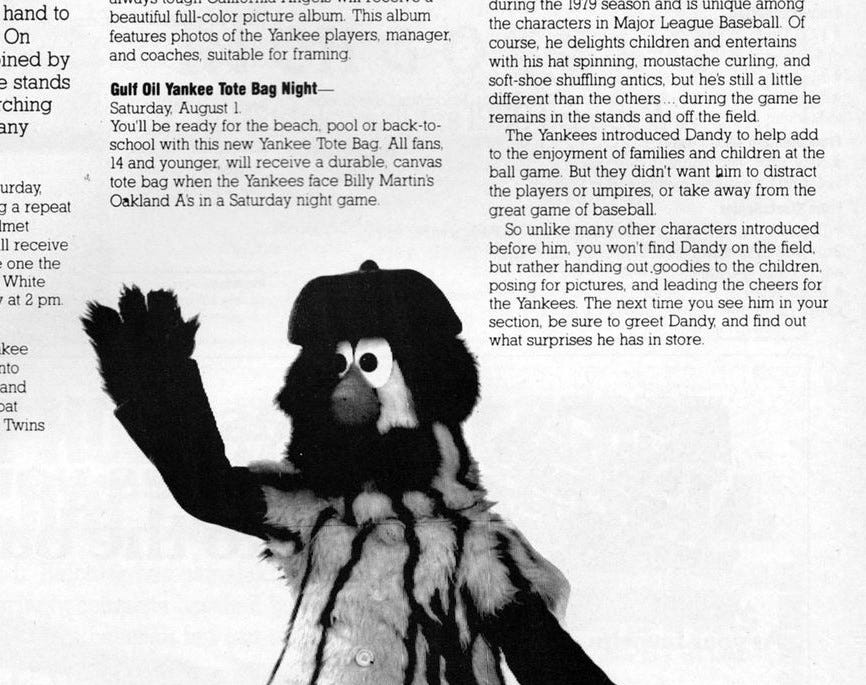

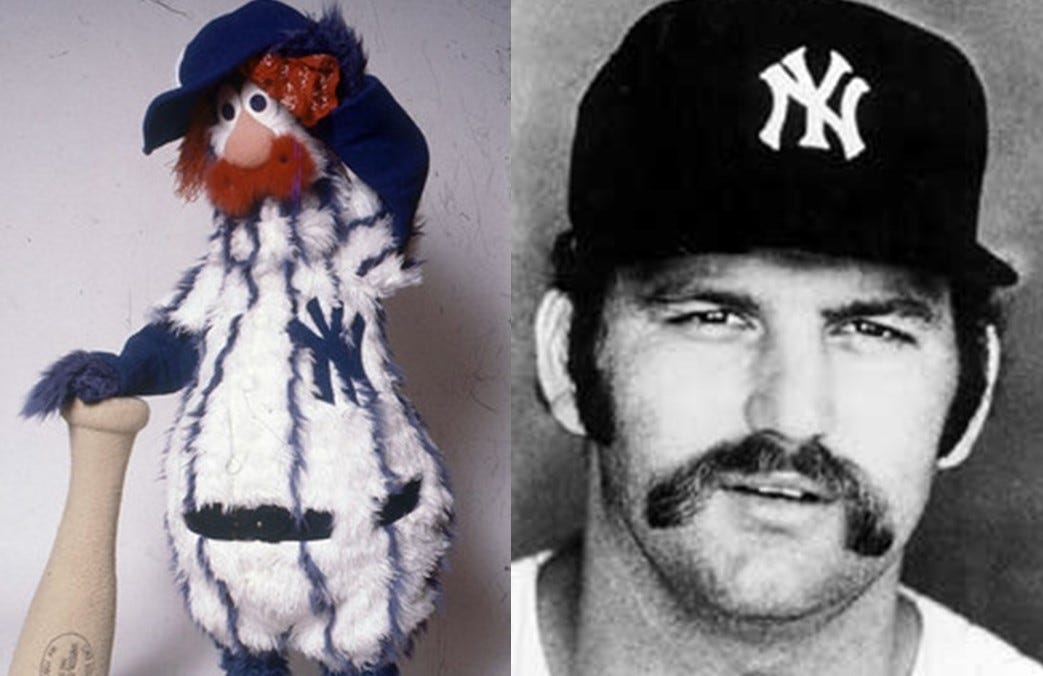

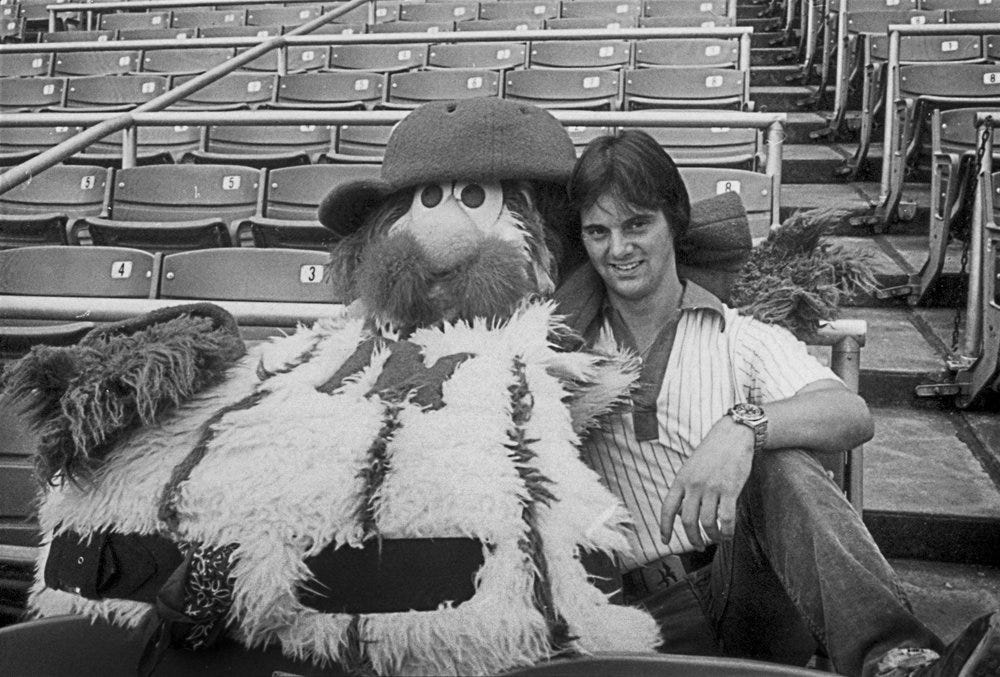

His name was Dandy. He was seven foot tall, with a rotund physique, a spinning baseball hat, a pinstripe Yankees outfit, and a ginger walrus-style mustache. He made his world debut forty-five years ago, on a warm July day in 1979 at Yankee Stadium.

“They originally wanted me taken out on the field in a truck and then I’d pop out of the roof,” remembers Rick Ford, who was hired to play Dandy at just 22 years old. “(Team organist) Eddie Layton had composed a song just for Dandy. It was going to be great.”

Instead, for his grand entrance Ford emerged from the stadium’s weight room, which doubled as his dressing room, and was led by a PR person directly to the stadium’s upper deck.

“I never got an introduction,” says Ford, who’s now 67. “Nobody had any idea what I was or what I was doing there. They just looked at me like, ‘What the hell is this thing?’”

If the name Dandy doesn’t ring any bells, you’re not alone. AJ Mass, author of Yes, It's Hot in Here: Adventures in the Weird, Woolly World of Sports Mascots and himself a retired New York mascot—he was Mr. Met during the mid-90s—was unfamiliar with Dandy until recently.

“My father was a huge Yankees fan,” says the native New Yorker. “And I never heard anything about the Yankees having a mascot.”

A 1998 story on baseball mascots from the New York Times was unable to find any Yankee representatives willing to acknowledge that Dandy ever existed. Yankees owner George Steinbrenner insisted he had “no recollection” of Dandy.

Even the Times’ own reporting couldn’t verify much, guessing (incorrectly) that Dandy roamed Yankee Stadium somewhere between 1982 and 1985. His tenure was actually between 1979 and 1981.

The only Yankees-sanctioned documentation that Dandy wasn’t just an urban myth is a 1981 Yankees game program, with a grainy photo of the mascot and an explanation that he isn’t allowed on the field.

Designer Bonnie Erickson, who co-created Dandy, isn’t surprised that the Yankees want to erase their failed experiment from history.

“They always struck me as a team that's very proud of their legacy,” she says. “Why would they want to admit that they tried something that didn’t work?”

The exact origins of Dandy are mostly left to speculation. Mass suspects that the huge success of the Phillies Phanatic, who debuted in 1978, fueled Steinbrenner’s decision. “George probably didn't like the idea of Philadelphia one-upping him,” Mass says.

Erickson and Harrison, who at the time had a puppet design workshop on 5th Avenue and 17th Street in Manhattan, say they were approached by Yankees front-office executives with the offer to make a mascot.

The pair had a track record that inspired confidence. Erickson worked with Jim Henson on shows like Sesame Street and The Muppet Show, designing classic characters like Miss Piggy and the elderly hecklers Statler and Waldorf. She and Harrison also created the wildly popular Phillies Phanatic.

The design team met with Steinbrenner only once, in his office to review their sketches. It nearly ended in disaster when the notoriously prickly owner took issue with the shade of blue on Dandy’s outfit.

“I did a design that I called a dyed-in-the-wool Yankee,” says Erickson. “The pinstripes were more of a royal blue. Steinbrenner wanted it to be Yankee blue, and we knocked heads about that.”

Although the executives standing in the background were horrified that anyone would be so combative with the Boss, Erickson soon convinced Steinbrenner that royal blue would read better on Muppet fur.

During Ford’s initial dry run in the costume, on a non-game day in a nearly empty Yankee Stadium in late June of 1979, Ford remembers that Yankee stars Reggie Jackson and Goose Gossage burst into laughter after setting eyes on Dandy.

“Gossage turned to Jackson and says, ‘Boy, wait till Thurman gets a load of this guy, he looks just like him,’” Ford remembers.

Erickson claims Munson wasn’t the inspiration behind Dandy. “I didn’t even know who he was,” she says. What little she knew of the Yankees was based on her research. “I looked at old photos of the team from the early 1900s, and many of the players in those days had big, bushy mustaches,” she says.

Just weeks before Dandy’s world premiere, there was a minor scandal that almost benched his Yankees career before it began.

During an early July 1979 game in Seattle, Yankee outfielder Lou Piniella became enraged by the San Diego Chicken, who was pretending to put a hex on the pitcher’s ball. He got so upset that he threw his mitt at the Chicken, and told reporters later that the mascot “doesn't belong on the field. Let him do his routine somewhere else. Don’t let him clown around out there where the players are trying to make a living. It’s distracting.”

Steinbrenner publicly echoed Pinella’s remarks, essentially demanding that mascots be banned from professional baseball.

“It was all over the news,” says Wayde Harrison, Erickson’s partner. “That’s not what we wanted to see as we were getting ready to unveil our own mascot. We were like, ‘Oh my God, we're screwed!’”

Dandy still got his debut, but with decidedly less fanfare. The plan, Ford was told, was to do a slow rollout. If the Yankees were going to have a mascot, he couldn’t appear to contradict Steinbrenner’s line-in-the-sand comments about mascot interference.

“There's a misconception that I was confined to the upper deck,” Ford says. “That’s not true. I could go anywhere in the stands, just nowhere near the dugout or the field.”

Ford found reasons to be hopeful. When he was first introduced to the team, he was given a less than warm welcome. He remembers an early-in-the-season meeting Billy Martin, who was in negotiations to return as the Yankees’ manager.

When one of the front office execs introduced Ford as the new mascot, explaining, “he’s going to be joking around with you,” Martin turned to Ford and said, “Don’t do that. I don’t take shit from nobody.”

But weeks into his new gig, Ford started to feel more accepted. He remembers one game where Munson approached him during a mid-inning water break.

“He winked at me and said, ‘You're doing a good job, kid,’” Ford says. “I'll never forget that for the rest of my life.”

But then tragedy struck. In early August, the 32-year-old Munson died when he lost control of the aircraft he was piloting and crashed near the Akron-Canton Airport in Ohio. It was a devastating loss for the Yankees, and the worst possible news for Ford.

“I showed up for work as usual and they said no, you’re not going out there dressed like Munson,” Ford says. “I knew I was in trouble.”

Even before Munson’s death, Ford felt like he had an uphill battle.

“I was winging it,” he says. “I had no idea what I was doing. Nobody at the Yankees gave me any direction. I was just making it up as I went along.”

It wasn’t exactly a lucrative gig either. Ford made $40 for every home game, which translated to a yearly salary of $3,240 (or just south of $14,000 in 2024 dollars). A far cry from the $50,000 salary (a six-figure sum today) the San Diego Chicken was pulling in during the same year.

“It was embarrassing because everybody thought I was making a fortune,” Ford says. “Steinbrenner was famous for paying all his players a hefty salary, so why would it be any different for his mascot?”

It didn’t help that Yankee fans had little or no idea who he was. “Nobody called me Dandy,” Ford says. “Nobody knew the name. They all called me the Chicken. They were like, ‘Hey, there’s the Yankee Chicken!’ Or sometimes just ‘Mr. Mascot.’”

He was contractually required to work with a bodyguard, because fans could occasionally get rough. “They gave me two bodyguards when the Red Sox came to town,” he laughs.

He remembers one incident where a man approached him, asking Dandy to sign a note for his son. “I can’t even move my fingers in this outfit, so I’m shaking my head no,” Ford remembers. “And my bodyguard is like, ‘Sorry, he can’t do that.’ But the guy keeps asking, ‘Oh come on, Mr. Mascot, it’s his birthday!’”

Ford finally managed to scrawl a large X on some paper. The father looked at it and exclaimed, “What the fuck is this?” Then he crumbled up the paper, threw it at Dandy and shouted, “Fuck you!”

It’s one of Ford’s favorite Dandy memories. “I felt like a real New Yorker,” he says.

So what happened? Why was Dandy retired with such extreme prejudice, never to be heard from again?

Munson’s death and Steinbrenner’s anti-mascot worldview are the most obvious explanations. But the reasons could be more complicated.

“I don’t think the Yankees of the ‘70s, the Bronx Zoo, were the right organization to have a mascot,” says Mass. “They were gruff, they were brawlers. They didn’t need a mascot. They were their own side show.”

David Raymond, who played the Phillie Phanatic till 1993 (and coached Ford during his first year), thinks the blame really came down to a lack of commitment from the Yankees. “They made the decision not to care,” he says. “Especially in New York, if they smell fear on you or you’re not even pretending to care, it’s a death sentence.”

But it wasn’t the Yankees who decided not to continue with Dandy after their lease expired in 1981. (They rented the costume for $30,000 for a three-year trial run.) It was Erickson and Harrison who ended the relationship.

“They wanted to re-sign,” says Harrison, who still co-owns the Dandy copyright with Erickson. “But they weren’t willing to pay for a security person anymore, and that wasn't a negotiable point with us.”

Part of it was the mechanics of operating the suit. “We’ve done appearances with Sesame Street characters and it’s more complicated than people think,” says Erickson. “When you're in a big, bulky costume, you need somebody to be your eyes and ears, to make sure you don't tumble down stairs or help you get out of it when you need a bathroom break.”

And at least for the Yankees mascot, there was always a chance of a violent attack.

At Ford’s last appearance as Dandy, for a 1980 Citibank pep rally at Madison Square Garden, hosted by Lou Piniella and Bill Cosby, he had to bring his own bodyguard—a friend he paid with subway fare—and he was still attacked by the thoroughly soused audience.

“I fell off the stage and they just lunged at me,” Ford says. “I heard somebody scream, ‘Unzip his head! Unzip his head!’ I was pretty scared.”

Rattled by the experience, Ford says he declined to return the Dandy costume until the Yankees paid him the extra fee and travel expenses he’d been promised for the Citibank show. The Yankees eventually paid up and then stopped calling.

“Nobody really explained why,” Ford says. “They were just done with me.”

He was replaced by a New York actor named Darren Edwards—my attempts to locate him were unsuccessful—and Dandy remained the league’s least visible mascot for two more seasons until Erickson and Harrison pulled the plug.

Dandy’s creators, who now run their operation out of Brooklyn, have a healthy sense of humor about their short-lived Yankees mascot. “He could have been a star,” laughs Erickson, who went on to design sixteen more mascots for teams from the Orlando Magic to the Montreal Expos.

Other than early sketches, she and Harrison expunged all traces of Dandy, shredding the costume before disposing of it in a dumpster in 2000.

“As with most character costumes, if you’re not going to use it and you don’t want to store it, you have to destroy it so it doesn’t show up on the street or in somebody's auction house,” she says.

There is one happy ending to Dandy’s story.

Shortly after Ford signed on to play Dandy in 1979, he had a blind date with a woman named Page that he calls “way out of my league.” Before they parted ways, he gave her his business card, which included a tiny sketch of Dandy.

Two decades later, Ford, still living with his parents in Connecticut and still a struggling actor, got a letter from Page. She’d stumbled upon his card in a box of old mementos and the drawing of Dandy made her laugh. “Do you remember me?” she wrote.

He did, and they soon started dating again. A year later, they were married. “Twenty-three years and we’re still madly in love,” says Ford, whose last acting gig was a murder mystery musical in New Jersey.

“Dandy never made me rich or famous like I’d hoped, but he helped me find my soulmate. So I still consider myself a pretty lucky guy.”