The Heart is a Lonely Ventriloquist

The strange saga of my childhood "ventriloquist dummy" period, and lessons from my father

During the fall of 1981, my ten-year-old brother announced that he was going to become a ventriloquist.

I will never forget the look on my father's face. Our family was gathered around the kitchen table, having a hurried breakfast before fleeing our separate ways, and my dad was trying to read the morning paper in peace. My brother and I sometimes blurted out whatever wild notion happened to pass through our brains, like a prepubescent think tank.

“If Indiana Jones can climb under a moving car,” we'd wonder aloud over our Boo-Berry cereal, “I don’t see any reason why I can’t.”

Our dad was smarter than that. He knew we were just trying to get his attention. So he’d just smile and nod, muttering something noncommittal like, “Whatever you think is best.”

But when he heard the word “ventriloquist” trickle out of my brother’s mouth, he somehow sensed this was different. There are a lot of valid reasons not to have children, but the one they never tell you is this: You may, at some point during your offspring’s life, need to talk them out of a career in ventriloquism.

My father, wise as he was, couldn’t find the right words to explain exactly why this was a bad, bad, bad idea. What could he have said? “Well, son, you know how some of the boys at your school get teased for doing things that the other kids think are uncool? Well, those are the nerds who beat up ventriloquists.”

He didn’t say that, of course. He just listened to my brother and rubbed his chin, but I could see the wheels turning behind his eyes. “You do what you want,” he finally said, returning to his newspaper. “Just don’t bring it in the house.”

I was stunned. Not by our father's unwillingness to stage an immediate intervention, but that my brother was spending his hard-earned money on a plastic dummy. We'd spent the last few weeks obsessing over the Johnson Smith catalog, our one-stop shopping source for x-ray specs, fake vomit, and ultra-realistic monster masks (with real human hair). We had a limited income and some difficult decisions to make.

Personally, I was still torn between the Build-Your-Own Hovercraft and the Motion Activated Fart Alarm. I relished the opportunity to make my enemies flatulate from a distance (the perfect crime), but how could I resist a product that combined my two favorite pastimes, hovering and transportation?

If I went for the hovercraft, I’d have enough left over to purchase a Life-Size Frankenstein Monster or the World’s Smallest Harmonica. Or, if I could scrap together the extra nickels, both. Oh, sweet lord, can you imagine? My very own golem with a mouth full of tiny harmonicas, wheezing some Muddy Waters tune? It was like the Johnson Smith Company had recorded my dreams, turned them into reality, and then made them available at prices affordable for a pre-teen budget.

My brother had his reasons for being lured to ventriloquism, they just weren't good reasons. It had something to do with an episode of The Love Boat, which featured a pair of ventriloquists played by Sid Caesar and Ruth Buzzi.

It was troubling enough that my brother was taking social cues from The Love Boat, but what really disturbed me was that we were allowed to watch The Love Boat at all. Isn't there a point when parents walk into a room, realize that their children are looking at Gavin MacLeod in short-shorts, and smash the TV screen with the closest blunt object? And then, if you know anything about parenting, you sit down with your child for a heart-to-heart talk about nautical safe sex and male camel toes.

I suppose it was for the best. Better my brother gets seduced by fictional ventriloquists and not the other sub-plot in the very same episode, in which a pair of identical twin sisters decided to swap fiancés. The Love Boat was many things, but it was not a wellspring of prudent life lessons.

There was no talking my brother out of his choice. He’d even picked out his dummy, carefully selected from a diverse selection of three. It came with a monocle and a top hat, and vaguely resembled Charlie McCarthy, if Charlie McCarthy had made some major career missteps and ended up addicted to pain pills, doing dinner theater in Michigan.

Of course, if my brother decided to do something, I had to imitate him. Never mind that I was two years older, and long past the age when an interest in ventriloquism, however casual, could be easily dismissed as “just a stage he’s going through.”

Not wanting to be too obvious in my plagiarism, I picked the next most appealing dummy in the Johnson Smith catalogue: a freckled redhead named Danny O’Day, dressed in a plaid jacket and bowtie.

One look at Danny and I already knew his backstory. He was the manager of a Cinnabon at his local mall, and he enjoyed playing the French Horn, chaperoning church social hayrides, and crying himself to sleep. He’d kissed a guy once, but it was in college and he'd had too many wine coolers, so he didn’t think it counted. His favorite karaoke song was “Playground in My Mind,” he’d seriously contemplated growing a mustache, and he’d eventually die in his mid-50s after a botched attempt at erotic asphyxiation.

Our friend Mike, who lived down the block, also caught the ventriloquism bug. (Apparently hack vaudeville routines, at least during the late ‘70s, were as contagious as Chicken Pox.) But by the time he got his hands on the catalog, there was only one dummy not yet claimed by my brother and me: Drunk Clown. We assumed, rightly or wrongly, that this was just the dummy’s stage name, and Johnson Smith wasn’t seriously selling children a plastic doll with cirrhosis of the liver.

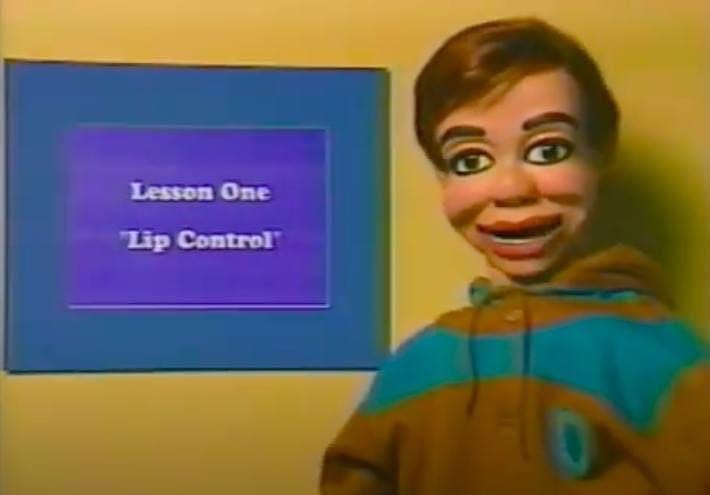

When our dummies arrived, we devoted ourselves to learning the craft of ventriloquy. I figured out how to make the doll’s mouth move, which really wasn’t all that difficult. You just stuck your hand into the gaping wound in its back and pulled the string.

As for the whole “lips not moving” part, I was clueless. My brother tried to give me pointers. “Say ‘v' instead of ‘b' and ‘t' instead of ‘p',” he told me. I just stared back at him. I didn’t have the time or patience to learn another language, but I wasn’t about to let him get all the glory. So I locked myself in my bedroom every night for weeks and rehearsed with Danny, mastering an exciting and innovative new form called Almost Entirely Mute Ventriloquism.

My brother was the first of our threesome to go public. He performed for a school talent show, and by his own admission, it did not go well. He didn’t get a single laugh, not even a pity laugh. In hindsight, his show business shunning may've had less to do with his ventriloquist skills and more with his comedy material. His entire act consisted of jokes that ended with the same uninspired punchline: “Don’t ask me, I’m made out of wood.”

After his shameful debut, my brother threw in the towel in disgrace. His dummy was put into permanent retirement, and because Mike and I considered him our canary in a coal mine, we abandoned our performance ambitions. Mike seemed especially relieved, as he was having trouble sleeping in the same bedroom with a clown with yellow teeth and bloodshot eyes.

But while the tide of popular opinion had turned, I opted to hold on to my ligneous companion. I had no interest in ventriloquism anymore, but it was still nice to have the company. I liked coming home from school and finding my red-headed cohort waiting for me. Sometimes, if I thought nobody was listening, I’d sit on my bed and tell him about my day.

I never mentioned Danny to my family. He was a secret, and I didn't expect them to understand. Actually, I didn’t understand. I was a little too old to be playing with toys, much less a toy that resembled an adult male with emotional baggage. Forget the inanimate object part of it, he just wasn’t an appropriate best friend for a 12-year-old. But he was a good listener. And it was easy to feel superior to him. I may’ve been insecure and painfully shy, but Danny was a grown adult living in a boy's bedroom with no discernable source of income.

“What’d you do with yourself today?” I’d ask Danny every afternoon. “Watched a few Sanford & Son reruns? Made some mac-and-cheese for one? Don’t worry, man, things are gonna pick up.”

Have you ever noticed how some pet-owners start to resemble their dogs? The same thing happens when you live with a ventriloquist dummy for too long. I never wore a plaid jacket or bowtie, but as the weeks and months went by, I noticed we had the same haircut and facial structure. Sometimes I’d look over at Danny, and it felt like I was glimpsing myself twenty years in the future.

I never had the courage to get rid of Danny. That ugly task was left to my parents. They didn’t make a big deal of it, thank God. They just waited until I went to school and then made it disappear. When I came home, it was gone. When I asked about Danny, they shrugged and feigned ignorance. There were no long talks about how “this hurts me more than it hurts you” or “we took it to live on a farm.” They just laughed and said, “Oh, that old thing? I didn’t even know you still had it. Hey, tell us again about that girl at school you think is cute.”

It was a master class in parenting. I mourned my plastic sidekick, but I eventually moved on, forgetting that I’d ever had an enfeebled, aphasic pal.

In 1957 – I was seven – I went to Sleepaway camp with Paul Winchel’s daughter. Naturally, dad brought Jerry Mahoney and Knucklehead Smit and put on a show. In 1975, I was in the same est training as Paul. I told him the camp story. He was speechless.

But seriously, I’ve long dreamed of doing an oral history of ventriloquism, including material from the dummy’s point of view.

One of these days…

LOLOL "prepubescent think tank"