The Moat, the Millions, and the $50 Timex Watch

My younger brother and I couldn't be more different—except for the grieving.

[Happy Thanksgiving, everybody! Here’s a story I wrote for the New York Times a few years ago, now with more words. It’s about awkwardly trying to reconnect with relatives and dealing with grief. So, y’know, all the things that make this holiday wonderful and awful simultaneously. If you’ve got family you still want to be around, hug ‘em while you can. And, if need be, wrestle with them across the back lawn to steal back the sacred talisman of your ancestors. It’s the Thanksgiving way!]

For most of the last decade, my brother Mark and his family lived in a house with a moat.

The house—a four-bedroom French villa in Bel Air previously owned by Jennifer Lopez and Marc Anthony—is pretty impressive even without the moat, but that unnecessary protective trench gives the house a certain surreal charm. It’s nice to know that when you visit your family for the holidays, you don’t have to worry about Spanish conquistadors.

When I tell people about my brother’s moat house, they ask, “Is he rich?” When I tell them he is, their next question is usually, “So you guys probably don’t get along anymore, right?”

It’s a weird thing to assume, especially the “anymore” part. It’s as if the moment my brother’s bank account added a few extra zeros (okay, a lot of extra zeros), he morphed into Monty Burns from The Simpsons.

I can’t blame them. For most of my life, everything I believed about rich people came from F. Scott Fitzgerald. “They are different from you and me,” he wrote in the 1925 short story “The Rich Boy.”

Despite not knowing any rich people personally, that seemed about right.

My family, on both my mother’s and father’s sides, has historically been middle class, usually on the lower end. We buy our cars used, find our clothes at outlet malls, and aren’t afraid of eating meat “priced for quick sale.”

I grew up with birthday parties at Burger King and the knowledge at eight that I’d be paying off college loans till I was 50. How could I disagree with Fitzgerald that rich people, with their lack of any discernible struggling, really did believe “deep in their hearts, that they are better than we are?”

Pop culture just confirmed all my suspicions. It was filled with reminders that the super-wealthy are unfailingly villains—Lex Luthor, Jabba the Hutt, the rich kids’ camp in Meatballs.

For every Richie Rich fantasy or pleasantly paternal Daddy Warbucks, there was a sneering J. R. Ewing or Smaug the Unassessably Wealthy, hoarding their stolen jewels and fending off hobbits. If you consumed enough media as a child and ever saw your parents get stressed out by bills, you hated the rich out of instinct.

Mark wasn’t born wealthy. If he did, I’d be wealthy, too.

My younger brother (two years my junior) got that way because he’s very good at making bad bets. He’s what some people have called a “doomsday investor.” He bets on market calamity, the financial disasters that nobody expects to happen. Every time you turn on the news and the stock market has taken another hit and the federal debt ceiling is on the verge of caving in, Mark just made another million.

He published a book about his investing philosophy, The Dao of Capital: Austrian Investing in a Distorted World, which I’m told is very good. I own a copy, and I’ve tried to read it several times. But given my limited grasp of all things financial, it might as well be written in Sumerian.

I asked him once what he does, and here’s how he explained it: “I exploit the distortions of our interventionist monetary policy as they manifest themselves in the financial markets. I do this specifically using very asymmetric payoffs of derivatives.”

Make sense? If it does, then you’re probably rich, too. I have no idea what any of that means. It might as well be the muted trombone “mwa mwa” of a Peanuts parent.

Either way, when the stock market crashed in 2008, Mark made a fortune. His hedge fund now has assets in the multibillion-dollar range.

How much of that is pure profit for him? I couldn’t begin to tell you. We’ve never talked about it. There’s just never an appropriate time to ask a family member, “No, seriously, how filthy rich are you?”

I know that earlier in his career, everything he owned was something I could also own. But then at some point, he bought the Bel Air home, a 1920 Lake Michigan log house and compound (complete with Chris-Craft boat), and a 200-acre goat farm in Northport, Michigan, the town where we grew up.

I make payments on a 2011 Honda CR-V, rent a three-bedroom apartment on Chicago’s North Side, and own up to six pairs of pants.

My brother and I aren’t just in different tax brackets—we’re in different universes.

Even before he crossed over, Mark and I weren’t exactly two halves of the same coin. He was a Republican by age 15 and ruined more than a few family dinners with his Reaganite free-market propaganda rants. I was a Democrat who marched in my first war protest long before I was old enough to vote and threatened to join the Peace Corps just to worry our parents.

Mark’s interests included tai chi, the Chicago Board of Trade, and Gustav Mahler. I was into punk bands from the ’80s, smoking weed, and not having health insurance.

When he suddenly had more money than Bruce Wayne, it seemed as if we had even less to talk about. I still adore him, but our lives became fundamentally different. During the 2016 election, I thought I was making a political statement with my Hillary bumper sticker. Mark hosted a $2,500-a-plate campaign fundraiser for Ron Paul at his house. Yes, the one with the moat.

But something changed a few summers ago. I was in Los Angeles on a business trip, and I spent the night at my brother’s place. I had dinner with him and his family, and then we stayed up way too late drinking very (very) expensive Scotch.

As we do every time we’re together, we try to reconnect, catching each other up on the recent happenings in our lives. He told me about an op-ed he wrote for the Wall Street Journal and talked about his favorite economists, like Ludwig von Mises and Frédéric Bastiat. I told him about a Trader Joe’s that just opened in my neighborhood, and how I’d already purchased a case of Three-Buck Chuck.

Then he glanced at my wrist, and his eyes narrowed. “Where’d you get that watch?” he asked.

The watch is a Timex digital with a stainless-steel wristband and a battery that has been dead since at least 1996, worth about $50 on eBay. He knew perfectly well where I got it.

“It’s Dad’s,” I told him.

There was a tense silence. “How much?” he asked.

It was a compelling question, especially coming from a guy with his net worth. I could have given him an outrageous figure, something with more digits than I’ve earned in my lifetime, and he might have said yes. But I wasn’t about to make it that easy.

“It’s not for sale,” I said.

He took a slow sip of his Scotch, pondering his options. He didn’t get to his financial position in life by giving up easily.

“I’ll wrestle you for it,” he finally said.

I nodded. “You’re on, bitch.”

If you have a brother, nothing about this will sound odd. This is how brothers interact. It’s how all major and minor disagreements are settled. Or at least it is among brothers who are between the ages of two and 18. But Mark and I are in our 50s. And one of us has a private tai chi instructor on retainer. (Spoiler: It’s not me.)

In 2002, Malcolm Gladwell wrote a New Yorker profile on Nassim Nicholas Taleb—Mark’s mentor and one-time partner at the firm Empirica Capital—that claimed Mark “exudes a certain laconic levelheadedness.” I wonder if Gladwell would still agree with his assessment if he saw my brother and me wrestling across Mark’s Bel Air backyard at 2 a.m., sweaty and grunting, Mark howling, “Give me the watch, monkey boy!”

Let me back up.

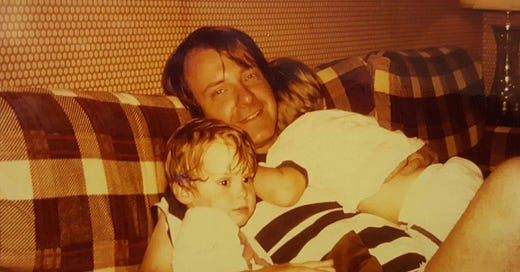

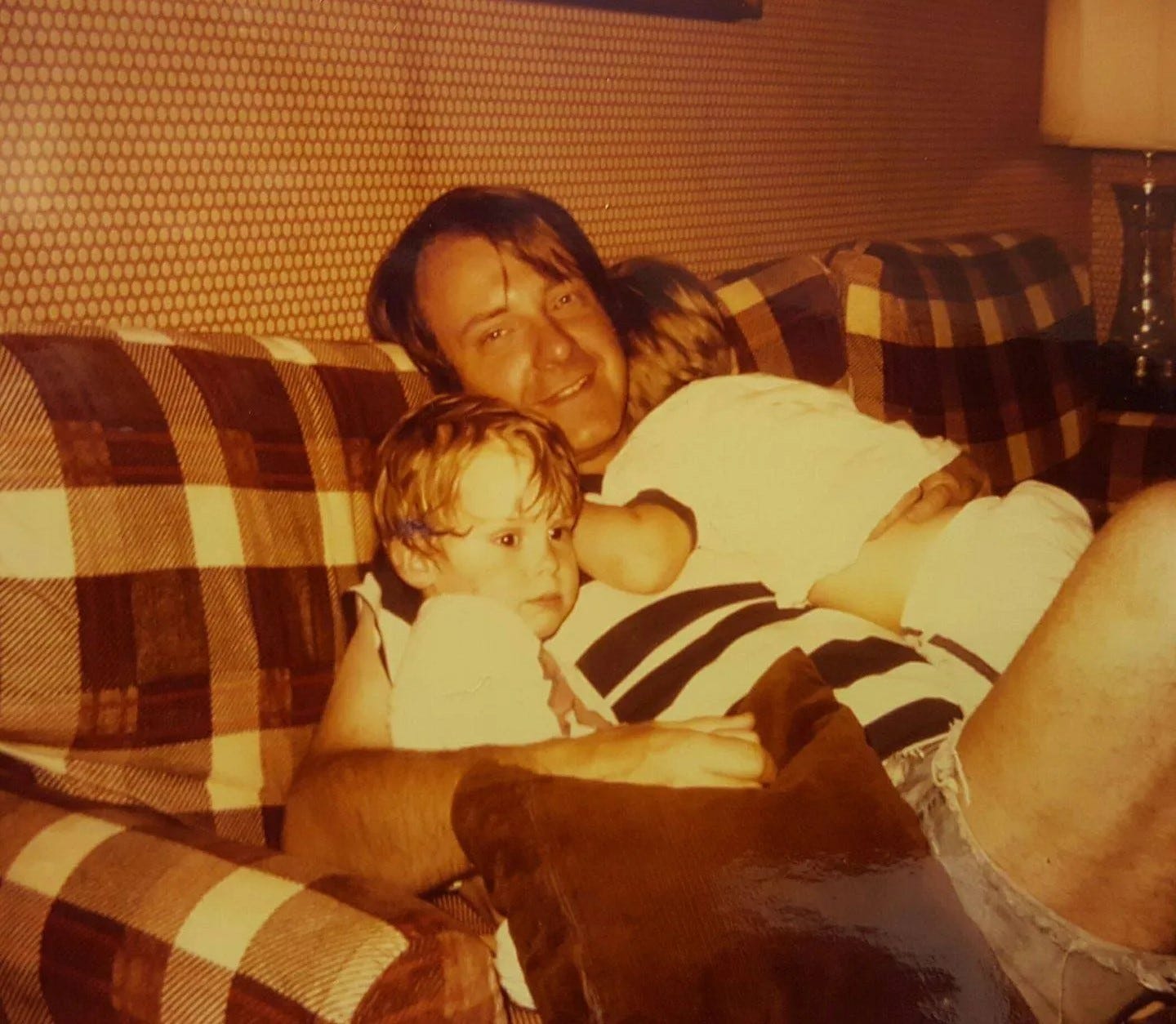

Our father died 25 years ago. It was unexpected, from an undiagnosed enlarged heart. Mark and I flew home to Michigan for the funeral, and our mom, still in a grieving haze, insisted that we haul away whatever we wanted from his belongings. So we took everything we could grab—pens, clothes, business cards—clinging to the minutiae of his life.

At some point during the weekend, as we sat on the floor of his office and did snow angels on a pile of his old sweaters, we wondered aloud what we intended to do with all this junk. We joked about dressing up a mannequin in Dad’s clothes and then forcing our future children to treat it as a living, breathing grandparent.

“You march up those stairs this instant,” we would bark at them. “You sit on your dead grandfather’s lap and tell him you love him. If I catch you sneaking out the window again, there’s no Disneyland for you.”

We laughed so hard at our ridiculous predictions. It made us feel less empty and sad about what we’d lost.

We divvied up Dad’s stuff, not really paying attention to who got what, and retreated back to our separate corners of the country. That was the last time we talked about it. Until two decades later, when Mark saw our dad’s watch on my wrist and decided he must have it.

He didn’t get it from me. Our wrestling match ended in a draw. After a few minutes of huffing and groaning, we limped back to our seats to drink more Scotch. But we kept right on arguing about that watch and who had rightful ownership. It brought old memories flooding back. We talked about our dad and recalled stories from our childhood we hadn’t thought about in years. The watch became a reason to remind each other of what we had in common.

Something shifted in our relationship after that. Our lives, at least on paper, have grown further apart. Mark left Los Angeles, moving his hedge fund to Miami and his family to a mansion in Michigan. He’s given up his moat for a hedge maze so large you can see it from space. I moved my family into a slightly larger three-bedroom apartment in Chicago’s slightly more northern side, which has the same square footage as my brother’s current walk-in closet.

Mark plays country squire on his Michigan goat farm, taking joyrides in one of his vintage 1960s dune buggies. I’m trying to decide whether I can afford subscriptions to both Hulu Plus and Netflix. He was interviewed on CNBC and Fox Business, talking about how he expects another stock market crash. I interviewed Ke$ha for Rolling Stone about her haunted vagina.

I will never make even a fraction of what my younger brother does. But I’ve never felt regret or misgivings that maybe I made the wrong career choice. “Do what makes you happy,” our dad always told us. It just so happens that asking Mike Tyson what a human ear tastes like is what makes me happy.

My brother and I still taunt each other about whatever priceless Dad artifact we’ve just uncovered and are unwilling to part with. He called me just to announce that he was wearing Dad’s penny loafers, which he assured me felt like sticking his feet in hummus, but would never be mine. I sent him a photo of the grandfather clock from Dad’s office, which has no working hands, and a note that read, “I will be buried with this.”

When our families got together for Thanksgiving, I brought along our dad’s childhood bear doll. The thing is 80 years old, at least half a century spent in a dank basement. It looks as if it has psoriasis, and it smells like old eggs. It should have been destroyed long ago, but it has value to us. Mark and I immediately launched into a fierce debate about who was promised the doll and how many lawyers my brother was willing to hire to bring it back to its rightful home.

Our respective wives and children ignored us, eventually wandering off to bed, leaving Mark and me to argue into the night. Nobody won. Nobody ever wins. Winning isn’t the point. When we play tug-of-war over our late father’s possessions, it isn’t about our dad at all. It’s about us.

At 3 a.m., we were still at it. My brother had to be up in two hours to call a billionaire investor in China. I had to be up at noon to call Dan Aykroyd and ask about that time he might have had sexual relations with a ghost. But none of it mattered because I had Mark in a choke hold, trying to keep him away from a moldy bear doll that probably had insects living in its belly.

“You’re never getting this,” I growled at him.

“Try and stop me,” he said, before thrusting an elbow into my groin.

I’m sure F. Scott Fitzgerald really believed that the rich aren’t like us. But he was wrong. In the middle of the night, when they’re mourning the things you can’t ever get back, fighting like hell to keep those memories alive, they’re exactly like us.