Would You Let This Man Give You a Tracheotomy?

The late Harold Ramis reflects on being the hero, saving the girl, and the futility of satire.

You may not have noticed but we just passed the ten-year anniversary of Harold Ramis’ death. Ten years! That still seems surreal to me. It was surreal that he died at all, to be honest. He’s somebody I just assumed would be around forever, becoming one of those old actors who goes on talk shows to share colorful stories from comedy’s golden age, or maybe (finally) reuniting with Bill Murray for a mostly improvised (and extra dirty) stage production of The Sunshine Boys. He at least needed to live long enough to put on Egon Spengler’s jumpsuit one last time for Ghostbusters: Frozen Empire, the latest reboot of the improbable comedy franchise, which hits theaters this Friday. I’m seeing the movie despite the lack of Ramis, don’t get me wrong. But his absence will feel like the itch of a phantom limb.

For a lot of us who grew up in the late 20th century, Ramis’ movies were comedy canon. Animal House, Stripes, Meatballs, Caddyshack, Ghostbusters, National Lampoon’s Vacation, Analyze This, Groundhog Day. I mean, Jesus Christ. And I haven’t even mentioned SCTV yet. Or the National Lampoon Radio Hour records, which only the nerdiest of the comedy nerds knew about (at least in my social circle.)

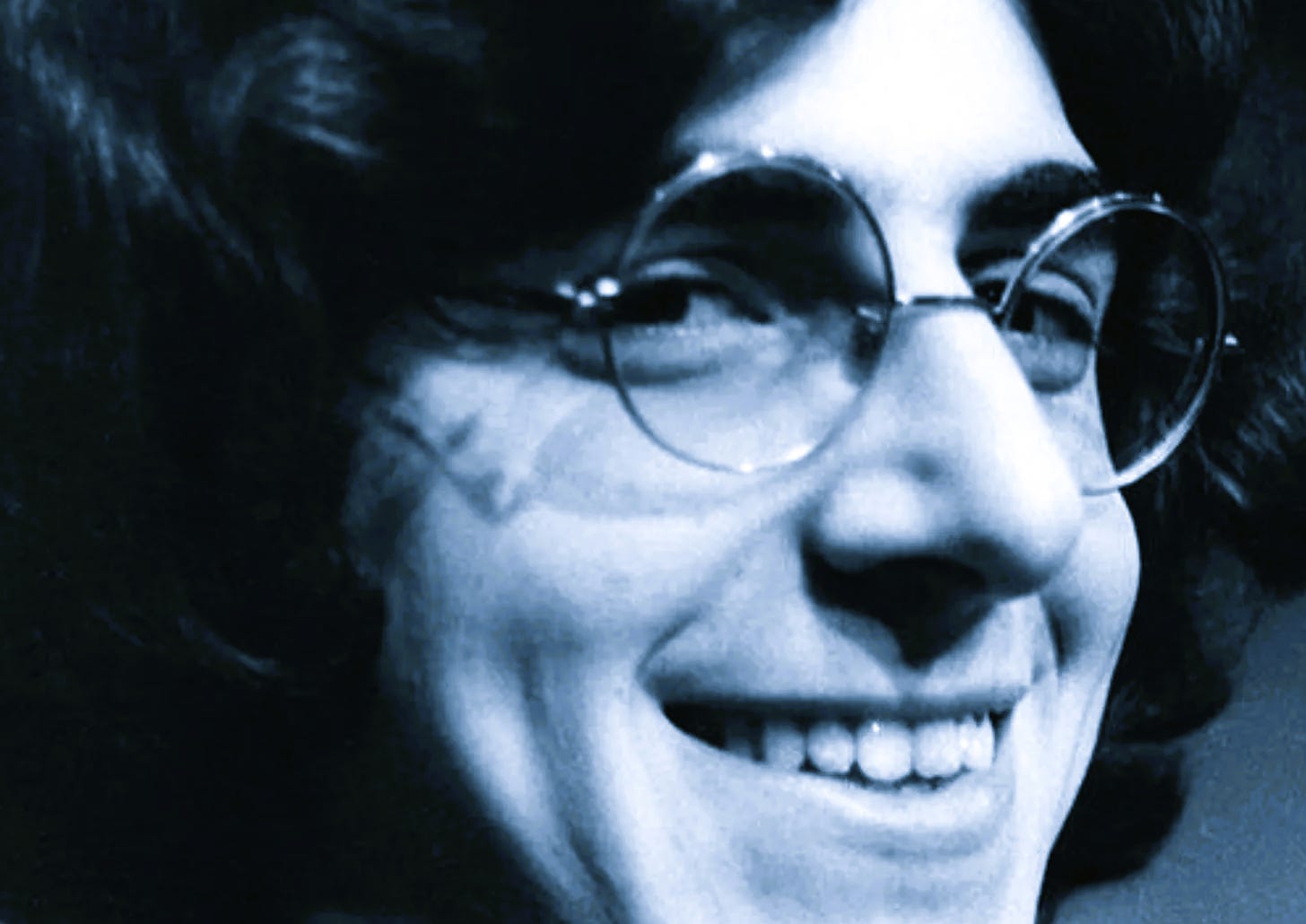

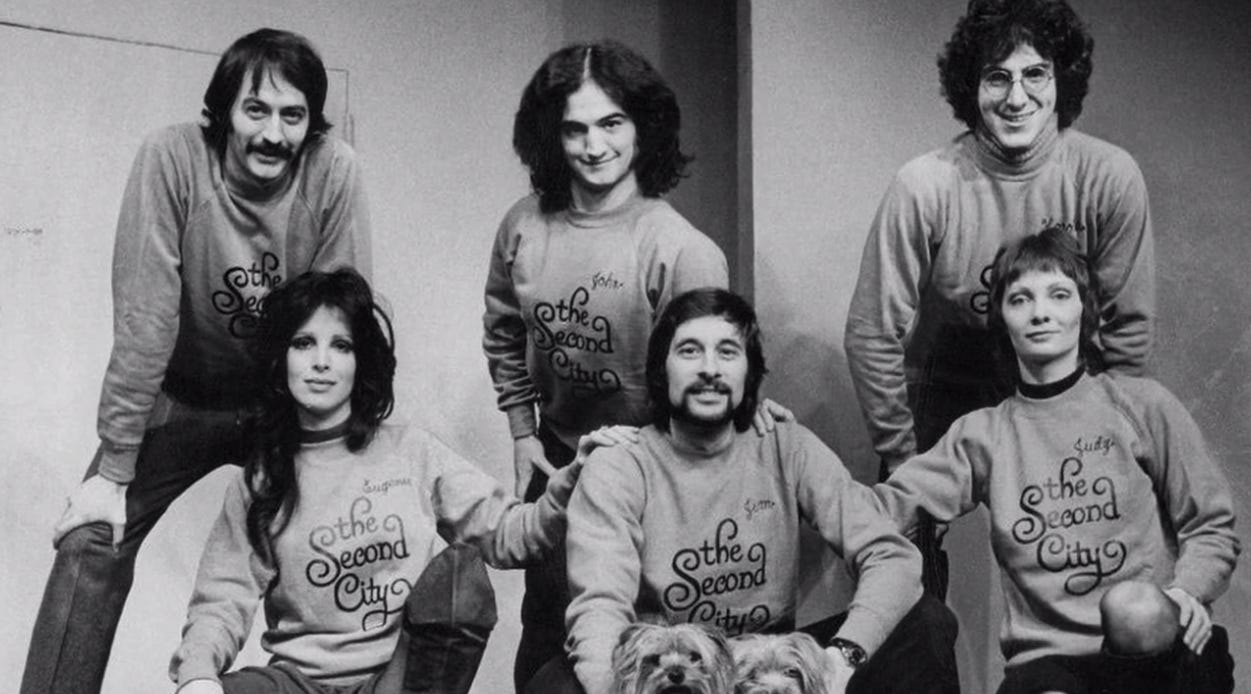

Part of the reason I moved to Chicago and started working at the Second City theater—I never got further than the box office—was to be like Harold Ramis. He wasn’t the funniest guy in the room, but he wrote all the best lines for the funniest guys in the room. I used to watch as tourists lined up for shows and admired all the framed photos of old casts on the lobby walls—“There’s John Belushi! There’s Bill Murray!”—without noticing the skinny bespectacled guy, the one who was actually responsible for all the classic one-liners they’d committed to memory.

I got to interview Ramis just once, almost a decade before he died. We talked for hours, and I still didn’t get to ask every question I had for him. I’ll ask next time, I told myself. Sigh. Such is life.

Eric Spitznagel: In your Second City cast, you were known as the smart, sensible one among maniacs. Dan Aykroyd said that you were the guy at the end of the party saying, “OK, that was fun, but now let’s take the car out of the pool.”

Harold Ramis: I guess it’s a fair assessment. I was the one you could trust to drive. Not because I was more sober, but because I was more controlled. For better or worse, there’s a certain amount of power that comes with being in control. It ties into why I’ve resisted acting. I realized that as an actor, you’re completely at the mercy of other people. You basically go begging for the opportunity to work. As a writer, at least nobody can tell me what to do. I can write what I want. I might not sell it, but at least I’m in control.

ES: Did this obsession with control come out of your experiences as a professional comedian, or was it something you learned at a young age?

HR: It was thrust on me by my parents before I even realized what I was turning into. I was the little guy who knew how to tie a necktie. It came from having absentee parents. They were tremendously loving and caring people who, by circumstance, had to go to work. So my brother and I were latchkey kids, left to ourselves. Instead of turning that into a delightful delinquency, we became overly responsible.

ES: Is that why you briefly considered becoming a neurosurgeon?

HR: Well, being the responsible young man, I thought I’d go to medical school. There was a TV show in the ’60s called Ben Casey, and I think he might’ve been a neurosurgeon. It seemed like a cool thing to do. When you grow up in Chicago, your whole family is counting on you to go to college and do something distinguished. The last thing you’re thinking is that you’re going to make a career in show business. I loved writing and performing, but the idea of doing it for a living seemed so remote. But I eventually let it devolve to the point where it was the only thing I could do. I left myself few other options. I made a handshake agreement with my best friend in college, Michael Shamberg, who is now a movie producer. We used to write shows together, and we said, “Let’s only do what’s fun. Let’s never take a job where we have to dress up in a suit.” He was like a surrogate brother to me. I drafted on his courage and confidence, or at least his bravado.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Spitz Mix to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.