You're Never Too Old to Weep Over the Dead Horse in NeverEnding Story

Were Gen Xers more traumatized by the movies and TV of our youth?

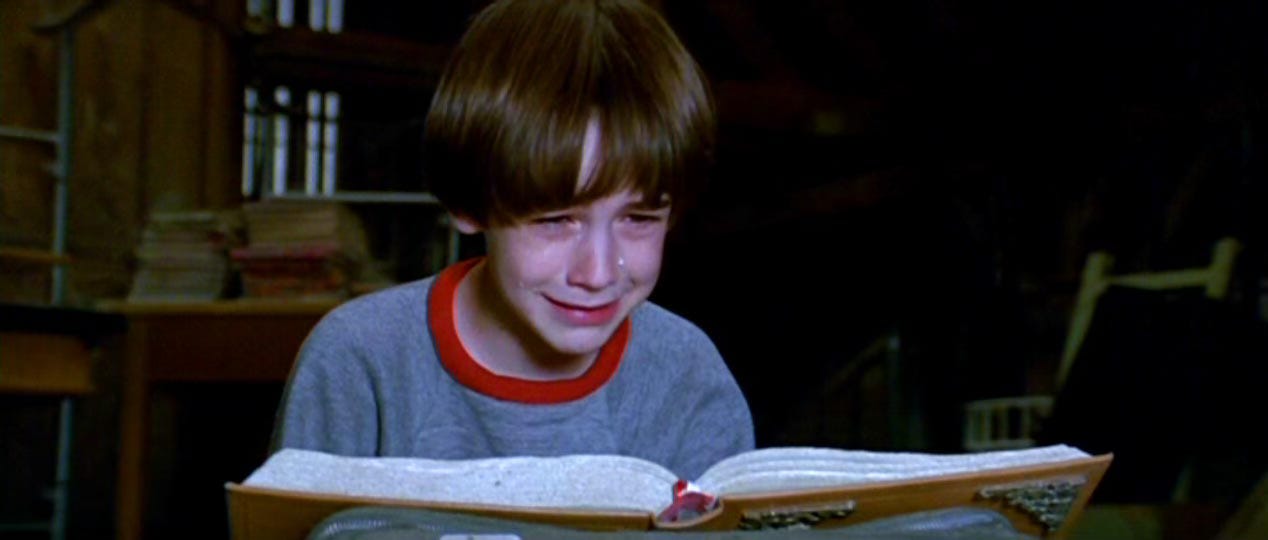

I really didn’t think I was going to cry this time. It’s been forty years since I first saw The NeverEnding Story in the theaters — it came out in 1984, when I was still a preteen — and I thought enough time had passed that it wouldn’t affect me. But then the tears started flowing.

If you grew up in the ‘70s and ‘80s, you know exactly the scene in NeverEnding Story I’m talking about. Atreyu and his loyal sidekick, a white horse named Artax, are traveling through the Swamps of Sadness. Artax gets stuck in the swamp and begins to sink, and Atreyu watches on helplessly, shouting at his old companion, “You have to try! You have to care!”

The scene wreeeeecked me back in the ‘80s, and apparently it still wrecks me in 2025. My son, however—a saucy 13-year-old boy who only agreed to watch the movie on my insistence—wasn’t as moved by the death of a fictional horse.

“What are you getting so worked up about?” He asked as I surreptitiously wiped away a tear. “It’s just a movie.”

Just a movie? Don’t tell that to the legions of oldies still haunted by NeverEnding Story memories. They’re everywhere online, from numerous Reddit threads devoted to the “collective childhood trauma” of Artax’s death, to TikTok, where one Gen-X user noted that the movie defined “so much of our personalities… and our therapy sessions.”

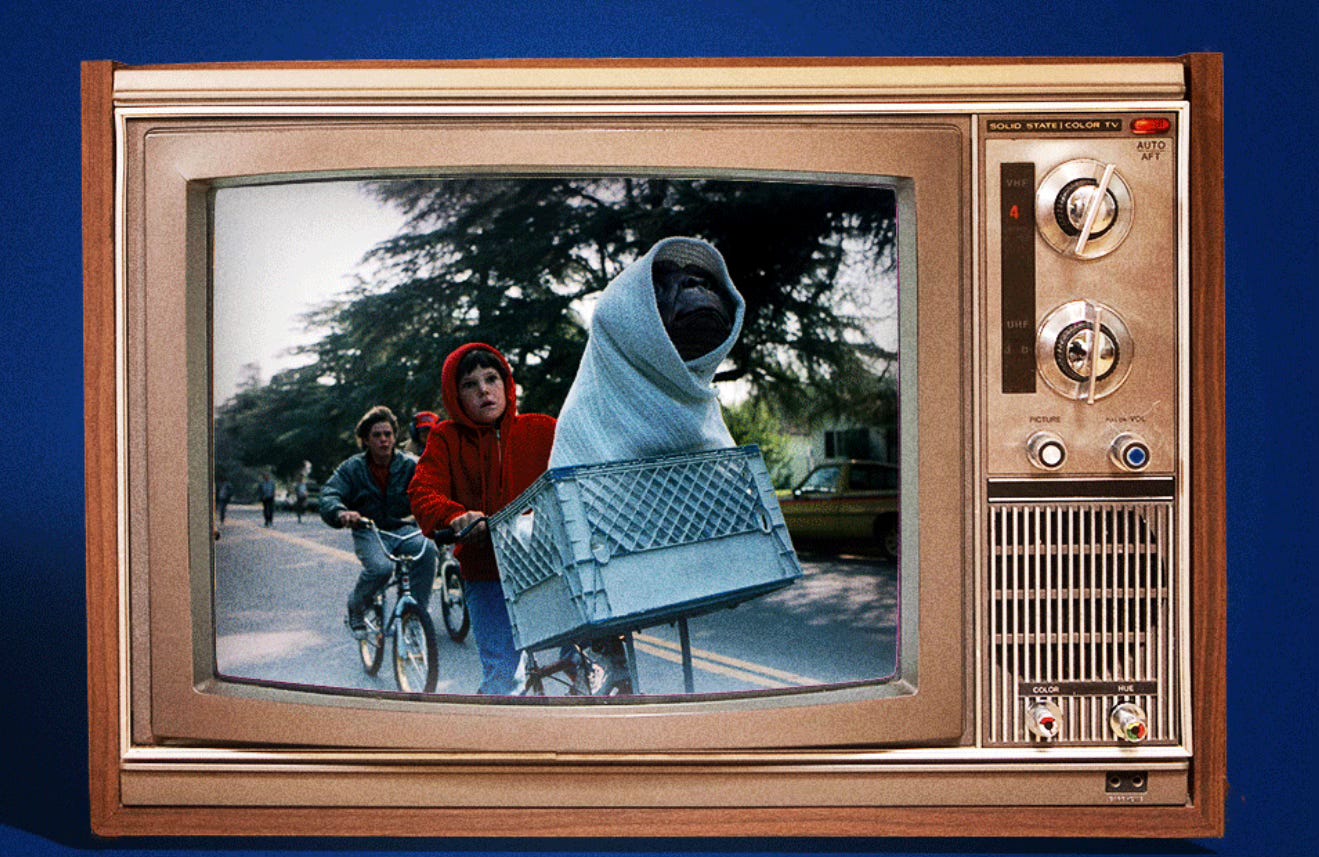

And it doesn’t end with Artax. Bring up traumatic movies with anybody over 40 and you’re going to get an earful. We love talking about the movies and TV shows we watched in childhood that continue to live rent-free in our brains, whether it was the kid-eating shark in Jaws, the decontamination tent scenes from E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, the nightmarish boat scene from Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, the face-melting bad guys in Raiders of the Lost Ark, or every single bunny death in Watership Down.

“There’s a running joke among Gen Xers that the movies and television they watched in their youth were darker than the media consumed by Boomers before them and Millennials after them,” says Shalon Van Tine, a cultural historian whose current research focuses on Gen X’s relationship with media. “Ask any Gen Xer and they will tell you that some of these disturbing images have remained imprinted in their minds forever, such as a puppy-like cartoon shoe being slowly dipped into a bucket of acid in Who Framed Roger Rabbit, or a skeksis draining the life essence from a helpless podling in Dark Crystal, or the creepy wheelers attacking Dorothy in Return to Oz.”

But are we really all that different from other generations? Plenty of Baby Boomers have vivid memories of being freaked out by the flying monkeys in Wizard of Oz. And my son and his teen friends insist that they’ve all been traumatized by the video game Five Nights at Freddy's. But somehow, the movies and TV shows that impacted Gen X left deeper scars. Or at least that’s what every group of 50-somethings at every dinner party I’ve attended in the last few years keep insisting.

The problem is, there’s not much research on the topic. Nobody was really studying Gen X and our relationship with pop culture back when it mattered. Recent research, like a 2023 study from the Netherlands, examined how movies can fuel social intelligence in children. But they focused on recent kids’ entertainment, like Inside Out, a 2015 film that makes Lidsville, a bizarro Sid and Marty Krofft show from the ‘70s, look like Taxi Driver.

As for the long-term effects of media on different generations, “we do not know a lot (read: nothing),” admits Rebecca de Leeuw, Ph.D., a Radboud University professor who authored the Inside Out study. But she suspects that movies probably do dig into our psyches in ways we don’t realize until much later. But how exactly? She’s not sure, other than confessing that she loved The Lion King as a kid and “I still cry when Mufasa dies.”

One theory for why Gen Xers have so many complicated emotions about our childhood entertainment is because we were essentially raised by it. We were, according to a 2004 marketing study, “one of the least parented, least nurtured generations in U.S. history." So we turned to TV and movies, with far more viewing options than our parents ever had, and almost no adult supervision.

Nobody was keeping tabs on how many hours of movies we watched, but as the New York Times reported in 1970, the typical 3-to-5-year-old American kid was watching “an average of 54 hours of television every week.” According to a May 2024 report from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychology, an 8-to-12 year old kid today gets between 28 and 42 hours of total screen time every week. Somehow we beat every subsequent generation despite not having our own tiny TV screens that we could carry everywhere.

But whether those numbers hold up to scrutiny isn’t really the point. Because what matters isn’t how much media we consumed, but how we consumed it. That’s according to Jean Twenge, Ph.D, a psychology professor at San Diego State University who’s studied generational impacts for more than 25 years. She’s also the author of Generations: The Real Differences between Gen Z, Millennials, Gen X, Boomers and Silents—and What They Mean for the Future.

“Gen X was the last generation to have a unified pop culture experience,” she explains. Our parents, the Boomers, may have watched the same movies together, but thanks to the cable channels and video stores that became ubiquitous during Gen X childhoods, “we could watch the same movies together over and over and over again,” says Twenge.

Millennials and subsequent generations had even more options—ever-expanding cable channels, the Internet, etc.—and their viewing habits became more disparate. “They didn't have that same experience where everybody was watching the same movies,” Twenge says. “And with Gen Z, nearly half of them prefer social video and live streams. Every TikTok feed is different. They’re not having shared experiences.

The shared experience is what made those pop culture memories burrow into our brains, and become something we identify as “collective” childhood trauma. We cry at the dead horse in NeverEnding Story not just because we found it sad, but because our peers were crying along with us.

“In essence, movies are no different from any other shared memory,” says Uri Hasson, a psychologist at Princeton University who researches what happens inside people’s brains when they watch movies together. Today, he says, people “live in their own separate bubbles, which are becoming more specialized and fragmented. Movies are just one way to create shared experiences, but as the number of platforms and movies increases, these experiences are becoming less shared.”

It’s not just the pop culture-inflicted trauma we carry with us. “We're also still rooting for Molly Ringwald to get the guy,” says Twenge. “We have an obsession with our pop culture that I think is relatively unique to Gen X.” Research does tend to back this theory up, with one generational analysis finding that Boomers and Millennials use YouTube mostly as a learning tool, while Xers prefer “rewatching old videos from their formative years (think high school years). Popular searches in their browsers include topics like ‘Six Million Dollar Man’ and ‘Prince Purple Rain’.”

“Our common language is pop culture,” says Twenge, who’s a Gen-Xer herself. “We saw a lot of the same movies together at the same ages, and a lot of the same TV shows at the same ages. You can sometimes strike up a conversation with someone by talking about the pop culture of our youth.”

I learned my lesson. I won’t be forcing my Gen Alpha son to watch any more iconic movies from my youth. I don’t need to be reminded that “the shark in Jaws is so obviously fake” or “David Bowie isn’t creepy or scary in Labyrinth, he just looks like an EDM DJ.” And I certainly don’t want to be told that crying over a horse sinking in quicksand is “no big deal” and “not something a grown man should be getting all weepy about.”

Unless you were there, watching NeverEnding Story on cable in the ‘80s for the hundredth time, because your parents were out late again and the TV was your only babysitter, you wouldn’t understand.