St. Patrick's Day Is for Day Drinking and Crying About Our Dads

A story about an old college friend, a few dozen beers, and the memories we can't let fade away.

“What was your dad’s beer?” Dan asks.

I hesitate, not because I don’t know the answer, but because it’s not a question I get asked a lot. Certainly not in a pub with a wide selection of craft brews with varying degrees of hoppiness.

It’s 8:30 in the morning on St. Patrick’s Day in Chicago. I’m not a fan of the holiday—drinking to excess while dressed like a slutty leprechaun just never appealed to me—but I’ve made an exception this year for my friend Dan Dowling. I’ve known Dan since college, which is roughly the last time I saw him. It’s been almost three decades since we’ve set eyes on each other, but I agreed to meet him at an overcrowded bar in downtown Chicago on the most highly trafficked drinking day of the year so we can toast our respective dead fathers.

“Miller High Life,” I tell him.

Even as I say the words, I can practically smell the beer. It smells like a hot summer day, sitting with my dad in the bleachers of Wrigley Field as we watch his beloved team lose yet again. I don’t think I’ve touched a High Life in years, at least since my dad died.

Dan flags down a bartender and orders a High Life for me and an Old Style, his dad’s beer of choice, for himself. We snap open the cans—no frosty mugs for us, we’re not trust fund babies—and raise them to the sky.

“I miss you, Dad,” Dan says, pointing his can towards the ceiling.

He’s not talking towards some arbitrary and theoretical heaven. He’s specifically addressing the ceiling. This bar, or at least a version of it, once belonged to his dad. The better part of Dan’s childhood happened between these walls, back when it was called Hobson’s Oyster Bar, and the decor was less tourist-friendly, the clientele were full-time drunks, and the bartenders didn’t dress like Hooters’ waitresses. St. Patrick’s Day was practically a High Holy Day. His dad would take him out of school to spend the afternoon with him at the bar.

It’s the reason Dan chooses this time of year to celebrate and remember him; every happy memory of his dad happened right here.

It’s also, ironically, the setting of his worst memory. It’s where a mysterious stranger walked up to his dad, pulled out a gun, and shot him dead.

I didn’t know that last part when I agreed to drink with Dan and get misty over our dads. But when he mentions it—casually, like it’s no big deal—it’s all I want to discuss.

Dan seems fine with it. Talking about his dad, even the ugly parts of the story, is the whole point of this yearly ritual. He tells me how it happened: It was 1983, and his dad was locking up Hobson’s for the night when somebody walked in and shot him in the back.

“Whoever pulled the trigger wasn’t trying to rob him,” Dan says. “He left the money in Dad’s pockets and didn’t touch anything in the bar.”

One theory is that it was retaliation. But from who? Possibly a local gang member with a score to settle, or a corrupt local politician who wanted his dad out of the neighborhood, or an irate former customer seeking revenge, or any number of other reasons why a tavern owner in seedy early-’80s Chicago might have an enemy.

I’m fascinated by the gritty details—it’s like a James Ellroy novel, told entirely from the perspective of a kid who lost his dad too soon—but I’m more intrigued about why Dan keeps coming back to this specific bar, where his dad met such a violent end. His family hasn’t owned the building since his dad was murdered—they sold it the very next day—and to hear Dan tell it, the space couldn’t look more different.

As we sip on beers, he gives me an architectural tour of what’s now called Snickers Bar & Grill, explaining how much has changed since his childhood, from the lack of tin ceilings (a common stylistic choice back in the good ol’ days of Chicago bars) to the alarming abundance of windows, which would’ve been heresy back in the day when the bar was frequented by lifer alcoholics and journalists—the Tribune and WGN buildings are a short walk away—who just wanted to enjoy a four-hour drinking lunch without the stupid sun reminding them of their bad decisions.

Despite the egregious upgrades, this spot is still sacred for Dan. It’s his Wailing Wall, his reminder of what he’s lost and what remains. It’s where his dad died, sure—and in a grisly way that most of us would want to forget and avoid—but even that heinous act can’t take away what this corner of real estate once meant to him. When he’s here and sipping on an Old Style, he can close his eyes and still hear the ghosts.

I’ve been struggling with how to do that. My dad died a quarter century ago—nothing as crazy as an unsolved murder; he was killed by heart disease—and every year my memory of him gets hazier. The photos get more faded, and the stories about him get told a little less often. I’m worried about him slipping away completely, that one day I’ll wake up and have no memory of what it felt like to be in the same room with him.

Another friend of Dan, a green kilt-wearing college professor named Chris, joins us at the bar. We order a second round of dad beers—an Old Style, a High Life, and a Coors for Chris’s dad, who passed away in January—and lift our cans towards the ceiling to salute them. We hold our ground as more bodies squeeze inside the small tavern, chugging their IPA bombers and small batch, green-dyed draughts. It’s way too loud and crowded in here, but we’re so immersed in our dad stories that we barely notice.

Dan talks the most, and we’re happy to let him. There’s something goosebump-inducing about listening to stories about his dad in the room where it happened. He tells us about being brought to the bar when he was just seven or eight years old and being put to work.

“I even had a little timecard,” he says. “For every hour I worked as a barback, I got a dollar. That was my allowance. I would make a hundred bucks a month, which is pretty good for a third grader.”

He learned how to set rat traps, rouse the sleeping drunks who lived upstairs, and carry beer up from the basement.

“At first I could only bring one bottle at a time, ‘cause I needed the other hand to grip the railing,” he says. “I became a man when I could carry a full case of beer up by myself.”

“It’s kind of weird that beer reminds you of your dad,” I tell him. “It’s not like you ever drank with him.”

“Oh no, I definitely did,” he says. “All the time.”

“When you were eight?”

“The deal was if my dad had a beer on the bar, I was welcome to drink from that. At the end of the night, if I was bored and wanted to leave, he’d say, ‘Okay, let me just finish this beer and we’ll close up.’ I’d grab his glass and chug it down, and he’d look over and say, ‘Hey, I wanted some of that,’ and he’d pour himself another. There were a lot of nights when I came home drunk. I was a skinny kid, maybe fifty pounds at most, so it didn’t take much.”

The best dad stories aren’t always the best examples of responsible parenting. All three of us have fond memories of our respective dads introducing us not just to our first taste of beer, but our first boozy overindulgence when we learned there is such a thing as too many sips from dad’s glass.

We try to top each other with dad tall tales, comparing notes on how much they let us get away with, and how miraculous it is that any of us are still alive, growing up in an era where being a good dad meant being vaguely aware of where your child was at any given moment.

Dan tells us about an especially scary St. Patrick’s Day, when he wandered onto a parade float parked outside his dad’s bar, found a comfortable spot to take a nap, and woke up hours later in the middle of the parade, several miles away. (When he popped out of the float, dressed in a full green suit—a St. Patrick’s Day gift from his dad—a shocked and likely intoxicated woman in the crowd shouted, “It’s a real leprechaun!”) The embarrassed float operators brought him back to the bar, apologizing profusely, but his dad was unflustered.

“He hadn’t even noticed I was gone,” Dan says.

We laugh and order more beer. I tell stories about my dad I haven’t told anyone in years, certainly not to people who never knew him. But with enough High Life in my belly, I can’t shut up about him. I’m pretty sure I’m going to do this again. Not at this bar, and probably not specifically on St. Patrick’s Day. But I’ll invite my male friends out for a drink, buy a round of their dad’s favorite beer, raise a toast to our fathers living and dead, and wait for the dad stories to come tumbling out.

There’s something about beer and dads that’s emotionally intertwined. A can of cold, cheap beer like dad used to love makes us feel like Norse Vikings, swinging flagons of mead, and bragging about Beowulf. Except instead of defeating Grendel’s mother in an epic battle, the heroes of our stories do things like stumble home drunk at 3 a.m. and wake up their sons for a sloppy but joyful “Danny Boy” singalong.

“Your dad seriously did that?” I ask Dan.

“Yep,” Dan says. “My mom would start screaming ‘Let Danny sleep’ and I’d be groggy and crying, ‘Leave me alone! I don’t want to sing!’ It’s the only story I have about him that ends with me crying.”

“Other than that time he was murdered.”

“Yeah, but that wasn’t his fault,” he says. “You can’t dwell on shit like that. It’ll kill you. I could feel sorry for myself, or mad that someone took him away from me, even though I’ll never in a million years find out who that someone was. Or I can remember the good stuff, like when he stumbled home from the bar and woke me up to watch movies.”

“That’s a good memory?” I ask.

“Dad was a big fan of black and white movies. He loved the Sidney Poitier film Lilies of the Field. And WGN would always have it on at some ridiculous hour like 4 a.m. So he’d scoop me out of bed, carry me downstairs, and we’d sit on the couch in the middle of the night and watch Lilies of the Field. I can remember him holding me, with a beer in his other hand, watching movies till I had to go to school.”

I never knew Dan’s dad. Hell, I barely know Dan anymore. But after downing a few dozen beers on this hallowed ground, I can absolutely feel his dad’s presence. I also feel like I have a better idea of what it takes to keep your dad’s memory alive. You have to be unafraid to walk back into those dark places and find what you can still recognize in the shadows. Even if it’s just a cold, cheap beer.

“Who wants another?” Dan says, his voice wavering. He’s either had too many or he’s feeling the tug of nostalgia.

On any other St. Patrick’s Day, I would’ve politely declined and gotten the hell out of there. I was way too buzzed for so early in the morning. But on that day, for his dad, and for mine, I was all in.

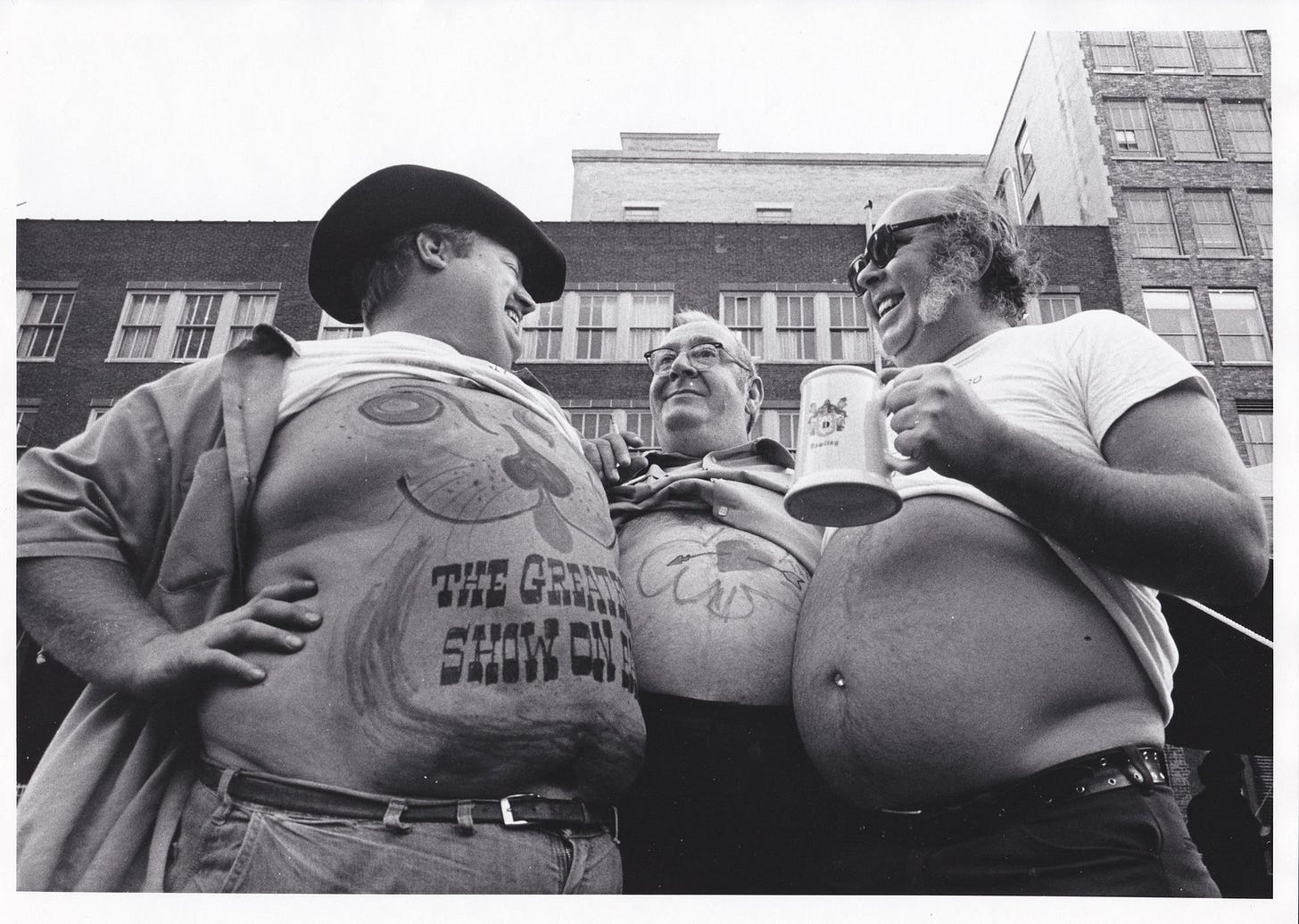

I would love to have been a fly on the wall…